The Man is an audio novel set in the first decades of the 20th century

The stories and original songs are written by Steve Gillette

Track 11. “There's a Cradle in Caroline”

Narration:

Frankie Trumbauer introduced Danny to Bix Beiderbecke. Bix was a cornet wizard, soon to become a legend. Frankie played the C melody sax in addition to the alto, which hardly anybody played and nobody could play it like he did.

Danny loved playing with those guys in spite of the keys like E flat and B flat that the horn players seemed to favor.

Once Bix went to dinner at his sister’s house, and his little seven year old niece was staring at him the whole time. Finally, he got a little self conscious and he said, “Missie, why are you looking at me like that?” She says, “I want to see you drink like a fish!”

© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

The Music:

“There’s a Cradle in Caroline,” music composed by Fred Ahlert and lyrics by Sam Lewis and Joe Young, was written in 1927. Frankie Trumbauer recorded “Cradle” and a dozen other songs with his orchestra for Okeh Records that same year. Many jazz legends are on those sessions; Bix Beiderbecke, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang, Don Murray, Tommy Dorsey and Pee Wee Russell.

Peter Eklund wrote the arrangement for our version of the song and played cornet; Dave Davies played trombone, Peter Davis played clarinet, alto saxophone and piano and Scott Petito played bass.

From the book:

Food prices have risen since the end of the war. In one ad I remember, it said, “One cent buys but a bit of meat or a bit of fish or a fifth of an egg, or a small potato, or a slice of bacon or a single muffin. One cent buys a big dish of Quaker Oats.”

Lorraine showed me a copy of Sour Grapes, a collection of poems by William Carlos Williams. I wasn’t sure I understood it, it seemed so straightforward and unpretentious, so un-poetic, but I like it.

In July 1925 a high school teacher, John Scopes, was put on trial for violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which had made it unlawful to teach human evolution in any state-funded school.

The trial drew intense public interest as two of the most famous lawyers of the day did battle. William Jennings Bryan, three-time presidential candidate and former Secretary of State, argued for the prosecution, while Clarence Darrow, the famed defense attorney, spoke for the defense. The case was seen both as a theological contest and as a trial on whether modern science should be taught in schools. It was the first United States trial to be broadcast on national radio.

Bryan fought against the teaching of evolution and social Darwinism. Darrow saw the trial as an assault on science. He said he “realized there was no limit to the mischief that might be accomplished unless the country was aroused to the evil at hand.”

The American Civil Liberties Union had decided to challenge the law. Its interest, like Scopes’s own, had nothing to do with religion and everything to do with free speech. (Scopes was himself a churchgoer and an admirer of Bryan, who had been the speaker at his high school graduation in Illinois in 1919.) The ACLU expected Scopes to be found guilty, after which they intended to take the appeal to a higher court.

Eugene Debs, who had been a longtime Bryan supporter, broke with him over this case. He referred to Bryan as “this shallow-minded mouther of empty phrases, a prophet of the stone age.” Clarence Darrow’s concern was for free speech, but especially in education. “I knew that education was in danger from the source that has always hampered it — religious fanaticism.” For his part, Bryan hated the notion that human beings were descended “Not even from American monkeys, but from old world monkeys.”

On day seven, it was so hot inside the courtroom that the judge moved the trial to the lawn in front of the courthouse. Darrow called Bryan himself to the witness stand, as an expert on the Bible. For two hours he questioned him. “Was the earth really made in six days? Had Jonah really been swallowed by a whale? If Eve was made of Adam’s rib, how did Cain get his wife? Bryan complained, “The only purpose Mr. Darrow has is to slur the Bible!” “I object to your statement,” said Darrow. “I am examining you on your fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on earth believes. We have the purpose of preventing bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States.”

The judge ordered Bryan’s testimony expunged from the record; the jury found Scopes guilty, and the judge fined him $100. Scopes spoke after the fine was imposed. It was the only time the court was to hear his voice. He said, “Your honor, I feel that I have been convicted of violating an unjust statute. I will continue in the future, as I have in the past, to oppose this law in any way I can. Any other action would be in violation of my ideal of academic freedom — that is, to teach the truth as guaranteed in our Constitution, of personal and religious freedom.” Five days later, William Jennings Bryan died in his sleep.

Rainy received a copy of Margaret Sanger’s book Happiness in Marriage. It’s a marriage manual, one of the first of its kind allowed to be sold in the U.S. I laughed self-consciously when I saw it. I clumsily said something like, “Well, I don’t think we need any help in that department.” But I watched Lorraine’s face for a clue as to whether she agreed with me. She laughed and said, “No, I’m writing a review for the Journal, it’s quite a ground-breaking book. I’m really focusing on the social implications. Although, you might want to read it, just in case.”

Just glancing through the chapter headings I saw several that grabbed my attention; Courtship for the Man, Courtship for the Girl, The Honeymoon, The Organs of Sex and Their Functions, The Drama of Love, The Rhythm of Sex, Psychic Impotence and Frigidity, Premature Parenthood and Why to Avoid it, Birth Control in Practice and The Husband as Lover. And I did read it cover to cover.

Lorraine had been a supporter of Margaret Sanger’s various campaigns since before I met her. Sanger was arrested in August 1914 for distributing copies of her pro-contraception magazine, The Woman Rebel, and she spent 30 days in jail in 1916 for opening a clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn, that dispensed the forbidden knowledge. She wrote that the jail sentence made her “birth control's martyr.”

In 1873, Anthony Comstock had created the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, an institution dedicated to supervising the morality of the public. He was able to gain the position of United States Postal Inspector, and he successfully influenced the U. S. Congress to pass the Comstock Law, which made it illegal to deliver "obscene, lewd, or lascivious" material, as well as prohibiting any methods of production or publication of information pertaining to the procurement of abortion, the prevention of conception, or the prevention of venereal disease. Even some anatomy textbooks were prohibited from being sent to medical students by the United States Postal Service.

Sanger became determined to challenge the Comstock laws. She proclaimed that each woman should be "the absolute mistress of her own body." Sanger coined the term birth control. She wrote: “The real hope of the world lies in putting as much painstaking thought in the business of mating as we do into other big businesses.” The government, she said, could not imprison ideas. She took on legislators who were under the sway of the Catholic Church, whose views on sex she said, ‘had not altered since Augustine laid them out in the fourth century.’

After one particularly tragic case, another instance of a woman in poverty trying to give herself an abortion, Sanger wrote: “I threw my nursing bag in the corner and announced ... that I would never take another case until I had made it possible for working women in America to have the knowledge to control birth.”

In 1922, she traveled to China, Korea, and Japan. In China, she wrote that the primary method of family planning was female infanticide. Later she worked with Pearl S. Buck to establish a family planning clinic in Shanghai. Sanger visited Japan six times, working with Japanese feminist Kato Shidzue to promote birth control.

In the fall of 1925, Bing Crosby and his cousin, Al Rinker, were ready to leave Seattle and head south to seek their fortunes in the entertainment business. They had a two-man act, piano and vocals. Al was a talented and animated piano player, and Bing had that surprising voice. Bing also played percussion on a cymbal sometimes attached to the end of the piano.

He had started as a drummer in their teen-age band, The Musicaladers, when they played for dances in a converted automobile showroom in their home town. He had a great sense of time, and even though he didn’t have a big voice he sang with wonderful rhythmic precision which inspired the jazz musicians he was to work with. He and Al would harmonize on the up tunes and then bring the energy down to feature Bing’s reading of some of the Gershwin ballads and torch songs of the day.

They had played in speakeasies and parties and fraternity bashes, and were determined to make their way into the big time. They left Seattle in an ancient and dilapidated Ford that barely held together and refused to start on the cold October mornings. The boys would have to take turns at the crank, and made many repairs to the worn out old tires.

They were headed to Los Angeles where Al’s sister Mildred had a home in Hollywood. She was married to a bootlegger, and was quite a fine singer herself, making good money in tips at a celebrity speakeasy in the Hollywood Hills above Sunset Boulevard. Al had not seen her for years, and had not let her know that they were coming, but she was delighted to see them. She was especially impressed when she could see that they had developed a real ‘act.’ She was able to introduce them around and help them to line up auditions.

We weren’t to meet them until they auditioned for Whiteman in 1926 when Jimmie Gillespie brought them to Whiteman’s dressing room at the Million Dollar Theater. The boys were so energized and enthusiastic about the prospect of joining the Whiteman orchestra. He offered them a five-year contract at $150 per week apiece with bonuses for recordings and special performances. He told them to take a few days to think about it, but they both practically shouted their approval of the offer. They were still under contract with one of the vaudeville houses until November, so it was agreed that they would join the group after that in Chicago.

Mary Margaret McBride was an American radio interview host and writer. She and Paul Whiteman collaborated on the book, Jazz. The book lent credibility to his reputation as the “King of Jazz.” The book is more of an overview of jazz history and the Whiteman band, and not a script for the movie, but it did help to get the ball rolling.

On December 21st and 22nd we went into the studio in Chicago to record several new songs. The studio was the enormous Orchestra Hall. It’s such an enormous space, and the reverberant sound was surprisingly good. The one recording that stood out was Ruth Etting’s song, “Wistful and Blue.” Harry Perrella played piano, Wilbur Hall played guitar and John Sperzal played the upright bass. This was the first time that Whiteman had used the upright bass in a recording.

Max Farley, our sax player, arranged the piece, but Marty Malneck wrote a special trio for the two vocalists and his own viola. This was the first time for Al and Bing to be heard on record. The last section of the song was sung in “scat,” that is, without words, but sound syllables instead. This was new for the group, but not for the Chicago jazz community in general.

Louis Armstrong had held sway in Chicago and the previous spring had recorded many of the Hot Five sessions. Those arrangements had featured liberal scat singing, in the vibrant style that was the Satchmo trademark. The Sunset Café, where Armstrong had led the band, was run by Joe Glaser who worked for Al Capone. Later he became Armstrong’s manager and went on to build the Associated Booking Agency. Since the club welcomed an integrated audience, and stayed open two hours later than any other club in Chicago, it became a second home to Bix Beiderbecke, Hoagy Charmichael, Tommy Dorsey, and Frank Trumbauer.

Bing and Al spent many nights soaking up the splendor of the Louis Armstrong experience. One night, Louis revived a routine he had created in New York two years earlier, when he put on a frock coat and dark glasses and became the preacher, Reverend Satchelmouth.

Another aspect of the Chicago experience in those days was the influence of “Mezz” Mezzro. Born Milton Mesirow, he played tenor sax and clarinet. When we met him he had played with the Chicago Rhythm Kings and Eddie Condon’s band. He worked with Benny Carter and Louis Armstrong too.

Mezz’s clarinet was not as eloquent as the ganja that he provided his friends. Marijuana was legal then, and was easily available. At one point Bing embraced it with a greater gusto than was perhaps wise, as he had done with alcohol, but after some rough edges on some of his vocals, he made an effort to keep it from affecting his work.

During this time, a few of us spent one wild night at a speakeasy on State Street known as the Three Deuces, named after the notorious New York brothel and gambling spot created by Johnny Torrio, known as the Four Deuces. Torrio was a graduate of the famous “Five Points Gang” in New York, and had moved west when police sought him for the murder of Herman Rosenthal in the sensational Becker case in 1912.

In the early days of prohibition, Torrio saw that there would be enormous potential for money in illegal alcohol if he could find a way to eliminate the competition. For that he called upon the talents of another “Five Points” debutante, Alphonse Capone.

Torrio offered Capone half of the profits from the new venture if he could take control of Chicago. Capone opened a modest office for appearances’ sake at 2220 South Wabash Avenue, and on his card it said that he was a “second hand furniture dealer.”

Within three years, he had an army of seven hundred men, with sawed-off shotguns and Thompson sub-machine guns. Eventually Capone was able to master the political element, and by the mid-twenties, he controlled the suburb of Cicero and had installed his own mayor and police chief.

Rival gangs such as the O’Banions, the Gennas, and the Aiellos all offered resistance, but none seemed to have Capone’s combination of organizational skills, ruthlessness, and luck. More blood flowed in the streets of Chicago than had accompanied any struggle since the Civil War. Capone ‘eliminated’ Dion O’Banion, one of his strongest rivals, but others of that gang continued to carry on the struggle.

On February 14th, 1929, at half past ten in the morning, seven of the O’Banion gang were at the S.M.C. Cartage Company on North Clark Street, waiting for a shipment of hijacked liquor. Three uniformed police showed up accompanied by two plain clothed men. This did not cause too much concern to the gang members, since most of the police were ‘friends,’ and even if they were arrested, they could expect to be released in a matter of hours.

As the police told the men to line up against the opposite wall, the two plain clothed men opened fire with machine guns. Gruesome photos accompanied the news stories that evening, and the story spread to most of the country.

The “St. Valentine’s Day” massacre, as it came to be known, was perhaps the most colorful of the incidents that occurred, but during that decade in Chicago, there were over five-hundred murders. Prohibition, or you might say, the public’s refusal to abide by it, had created a monstrous syndicate of crime.

There were ten-thousand speakeasies in Chicago alone. And although it’s strange to admit it, they contributed to the rise of the musical form that we had all come to call “Jazz.” It was said that many of the gangsters loved the music, and had their favorite performers. Some offered protection and career advancement, and there are several very well-known entertainers who would have to admit to their embarrassment, that they might not be where they are without the help of a powerful mobster. But then, they might not be anywhere if not for that special protection.

It was against this background that I was swept up in the excitement, if not the danger, of Chicago. On the night I speak of — one incredible jam session at the Three Deuces, I was treated to a new experience.

Mezz was a familiar figure in the Chicago jazz clubs. I had not met him yet, and when he showed up, I didn’t know who he was. I assumed he was there to play, which he was. But he was also there to share some of his extraordinary herbal medicine, what common parlance referred to as pot or ganja or hop.

It was William Randolph Hearst who had given it the name Marijuana, at a time when he was doing battle with Pancho Villa over thousands of acres of land, and found it expedient to identify the plant with Mexican people in a larger campaign for control of agricultural labor and to advance several other aspects of his corporate agenda.

I had been aware of the plant, but had never experienced its effects. I had been in the presence of musicians who were under its influence, and I was not impressed by any special augmentation of their musical skills. Really, my impression was that the opposite was true. I could see no reason why anybody would want to put themselves under its odoriferous spell.

But this was an extraordinary night. Hardly anybody seemed to be concerned about the clock, or business of any kind, it was a day off, and a night to howl. I was in pretty good tune, and was really enjoying the chance to sit in with these guys whom I so much admired. I was always pleased when I felt that I was accepted and that the roles of the organization didn’t interfere with the spirit of improvisation.

Partly in that spirit, I didn’t refuse as I had done before when the burning bush was passed to me. I took my turn and checked my tuning, and contributed to the jokes and banter, and took my turn again when it came around. Soon, I began to have the curious feeling that I was getting more from the music than I was accustomed to expect.

There was a definite sense of a shimmer, a glow, a sweetness to the sounds that were reaching my ears. Ears which seemed to be a little removed from the space we were all in, in an unexplainable, but not unpleasant way. A sense much like tunnel vision, gave me the feeling that I could bring the strings of my guitar to life, that I could set them ringing in voicings and sonorities that were authentic in some new way.

When it was my turn to be heard from, in support of another player, or when supported by others, there was a strange new sense of conspiracy, of secrecy, of this moment being everything there was and this little band, the only people in the world.

Conversation almost entirely disappeared, but the playing truly became our conversation. Bing found lyrical interpretations that went beyond anything I had remembered of earlier performances, the songs themselves seemed to have gained a depth of poetic insight and it surprised me that I had not been aware of it before.

As I came to understand, so many of these impressions were simply the effect of the smoke, and I learned that there were many good reasons not to let it become a habit. Still, I’d have to say that I did have a wonderful time, and as Bix and Bing claimed later, “everybody was a genius that night.”

I headed home to New York for the holidays as soon as the sessions were over. It was wonderful to arrive at Grand Central on Christmas Eve, to a beautiful fall of snow on the city, a fire in the fireplace, and a reunion of our little family.

© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

To Track 12. “Creole Belle Medley".

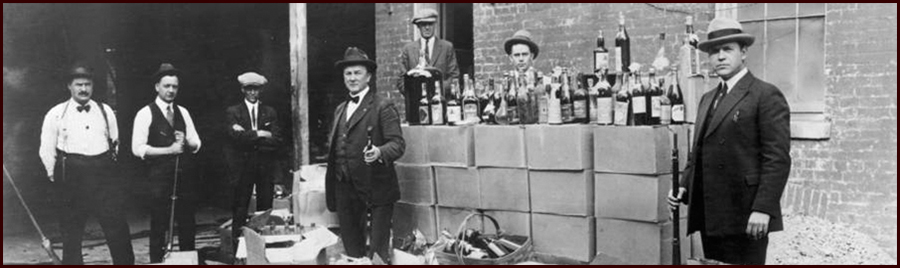

Federal Revenue agents with captured liquor.