The Erl King Words and music by Steve Gillette from the poem by Goethe

The folk music revival came along at a time in my life when I was just beginning to come to consciousness in many ways. Having weathered, well mostly sat out, the dating ritual of teen-age years, I was beginning to move on to a wider world of experience including history and mythology.

I mention mythology specifically because, as we found in the discussion of the work of Carl Jung, there was work to be done to individuate myself and to engage in the dialog with my own unconscious resources. Not to mention irrational fears and inhibitors to be confronted on my way to maturity.

The music of the fifties was mostly movie themes and puppy love. Even rock and roll was innocent of any troublesome revelations about the powers that be or the injustice of racial and class inequities. If the messages were there, they were submerged in the subtext of hipster-speak, which I wasn’t to decipher until well into the next decade.

In a college choir class, the professor showed a little movie of Joan Sutherland singing the Schubert setting of “Erlkönig,” the poem by Goethe. The German language went right over my head, and the music seemed stilted and dark, but the professor’s reading of the literal translation of the poem definitely connected with something in me.

I’ve wondered if some psychologists might have found that significant of my unique character, but then I’m sure that the piece has had a wide appeal and not all of those responding to it would be bent in the same way. Let us just agree that there are possibly deep psychological reasons why some stories reach us and seem to resonate.

With the translation I had the beginnings of my own setting of the poem. I just worked with it enough to pull together a rhyme scheme. I explored the colors of chords that I cobbled together in my own way in a tuning that I thought offered all the darker hues of what I felt was the mood and subtext of the poem.

The tuning is DADGAD which is a very common tuning for Irish and Celtic tunes, especially accompanying fiddles which often play in the keys of D or A. With modal tunings, there is the additional attribute of chords without the third so that the harmony isn’t defined as major or minor.

Cindy once mentioned that when, as a teenager, she first heard Child ballad 20, “The Cruel Mother,” she interpreted it from the standpoint of the two infants who are sacrificed by the young mother who had been betrayed by her father’s perfidious clerk. But later in life, she has come to have empathy with the mother, at least to understand the historical context of the ballad, and what it meant to be an unwed mother at the time.

“Erlkönig” is believed to be Danish in origin and derives from ellekonge or elverkonge meaning “King of the Elves” in Danish folklore. Goethe’s poem takes it name and story from earlier tellings of the mythic tale.

The New Oxford American Dictionary follows this explanation, describing the Erlking as a bearded giant or goblin who lures little children to the kingdom of death. According to Danish legend old burial mounds are the residence of the elverkonge.

In the original Scandinavian version of the tale, the antagonist was the Erlkönig's daughter rather than the Erlkönig himself; the female elves or Danish elvermøer sought to ensnare human beings to satisfy their desire, jealousy or lust for revenge. The name is first used by Johann Gottfried Herder in his ballad “Erlkönigs Tochter.”

Interpreters of the Herder ballad suggest that the daughter acted out of anger over a betrayal, possibly infidelity, which brings the story into alignment with the Greek tragedy “Medea,” although a central element of that story has to do with the woman taken from her homeland and family by a man who leaves her for another woman. She takes revenge by killing their children.

Although inspired by Herder's ballad, Goethe departed significantly from both Herder's rendering of the Erlking and the Scandinavian original. The antagonist in Goethe's "Erlkönig" is the Erlking himself rather than his daughter. Goethe's Erlking preys on children, and his motives are never made clear. Goethe's Erlking is much more akin to the Germanic portrayal of elves and valkyries as a force of death rather than simply a magical spirit.

In the poem and in my song, the young boy is being carried at night by his father on horseback. As the poem unfolds, the son claims to see and hear the Erlking and his daughters. His father doesn’t see or hear them and he attempts to comfort the boy with explanations from nature, the night wind, a passing cloud, the willows.

The Erl King attempts to lure the child to come away with him with promises of gold and jewels and the sweet favors of his daughters. The father is helpless to console the frightened child, and by the time he reaches his destination, the boy is dead in his arms.

The poem has been set to music by many composers, with Franz Schubert's rendition being the best known. Probably the next best known is that of Carl Loewe in 1818. Earlier versions include Corona Schröter in 1782, Andreas Romberg in 1793, Johann Friedrich Reichardt in 1794 and Carl Friedrich Zelter in 1797.

Ludwig van Beethoven attempted to set it to music but abandoned the effort; his sketch was completed and published by Reinhold Becker. Other versions are by Václav Tomášek, Louis Spohr, Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst, and recently Marc-André Hamelin.

Schubert’s setting starts with the piano playing rapid triplets to create a sense of urgency and simulate the horse's galloping. The triplets continue throughout the entire song except for the final three bars and mostly comprise the uninterrupted repeated chords or octaves in the right hand.

Each of the Son's pleas becomes higher in pitch. Near the end of the piece, the music quickens and then slows as the Father spurs his horse to go faster and then arrives at his destination. The silence draws attention to the dramatic text and emphasizes the sorrow of the Son's death.

Nothing about my setting is nearly so sophisticated, although I was just a couple of years older than Schubert was when he wrote his first setting of the poem at 17. Mine is a more folky, improvised treatment that came out of what I like to call ‘guitar meditation.’

That’s just a lofty way of saying ‘noodling’ on the guitar until some ideas emerge that reinforce the emotions that are suggested by the story. This is a very common approach to songwriting, and is very useful as long as the listener doesn’t have to sit through the unedited process of development of the song.

The tuning was a big help in this exploration. The droning of open strings allow for a mood to be sustained while melody notes are discovered using the guitar like a dulcimer, moving voices against the drones.

The song served me well in my early days of live performance. And when Ian & Sylvia recorded our song “Darcy Farrow” and recommended me to Maynard Solomon at Vanguard Records for consideration for a recording contract, I’m sure “The Erlking” carried some weight. This seems to be indicated by Maynard’s choosing it as the opening song on my album.

It’s a very spirited rendition. I had not been used to working with accompanists. Dick Rosmini was a good friend and mentor, and he and I worked on arrangements for some of the songs prior to my signing with Vanguard. When our sessions were scheduled, Dick flew to New York to play guitar on the record.

At the same time, unbeknownst to me, Maynard had asked Bruce Langhorne to play guitar on the sessions. What an embarrassment of riches to have these two giants there to help me put the songs across. After a little bit of awkwardness about both of them adapting to the idea of sharing sideman duties, they amazingly fell into a very compatible groove, making room for each other’s ideas and honoring inspirations as they came up.

Russ Savakus played bass on the session where we recorded this song, and Bill Lee, Spike Lee’s dad, played bass in the subsequent session a week later. Some of the collaborations worked better than others, but when the tape began to roll, we were all locked in, and were pretty happy with the result.

Here is an animated video from Lacrimozart, that has subtitles and a fine performance by the lyric baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and pianist Gerald Moore.

Der Erlkönig Schubert Animation

Performed by the lyric baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

and pianist Gerald Moore.

And here’s my video treatment with the track from my Vanguard album.

"The Erl King". Video by Steve

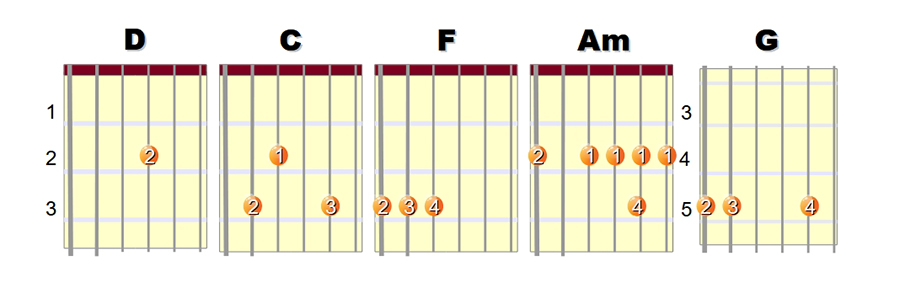

Because of the tuning, the chords needed to be re-configured. Here are the chords I use. With the capo on the third fret, the resulting key is F minor.

“The Erl King” — Words and music by Steve Gillette from the poem by Goethe

The

He

The Erl King beckons to the terrified boy,

You must come with me.

I'll give you jewels and wealth untold,

You'll walk in robes of bright and shining gold.

Father, father, do you not hear

The Erl King whispering low in my ear.

Hush now and rest ye, it's nothing my child

But the trees in the night wind playing their melody wild.

The Erl King says, oh, come with me

And my own fair daughters will wait on thee.

A heavenly vigil o'er your cradle they'll keep

And tenderly sing and rock you to sleep.

Father, father, see them there

The Erl King's daughters with bright shining hair.

No, my son, there are no fair maids

Nothing but the willow that wave in the glade.

Clutching the reins in his trembling hands

With pain and despair that he can't understand.

Alone on the road with the stars overhead

Fearful and hopeless, the boy in his arms is dead.

To the trees in the night wind he cries aloud

He seeks out the face of death in every passing cloud

Down in the meadow where the boy’s grave is laid

Nothing but the willows that wave in the glade.

Nothing but the willows that wave in the glade.

© 1966, Cherry Lane Music, ASCAP