The Man is an audio novel set in the first decades of the 20th century

The stories and original songs are written by Steve Gillette

Track 12. “Creole Belle Medley”

Narration:

When Danny started hearing recordings of other guitar players he was fascinated by all the ways there were to play. But left on his own, he’d gravitate toward what they called country blues. He especially loved the finger-style players – the drop thumb alternating bass where the thumb would keep the bass going while the fingers played melodic elements and counter melodies and harmonies. That’s what you’d hear him playing in an unguarded moment.

He might not have realized that Jack was doing something similar with the stride left hand on the piano, octaves and tenths. Mississippi John Hurt had a hit record in 1927 with a song called, “Avalon.” Danny learned a lot of his tunes including this one, “Creole Belle.”© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

The Music:

“Creole Belle” was written by J. Bodewell Lampe and George Sidney in 1901. It’s a very good piece to play with that drop-thumb, syncopated fingerstyle pattern that you can hear in a song like Doc Watson’s “Deep River Blues”. Another is Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train”. She calls her style of guitar ‘cotten picking,’ and she plays the guitar left handed but with the strings in the normal orientation, so that her finger plays the bass and her thumb, the treble strings. She explains that along with her banjo technique on the video. Here’s Mississippi John Hurt’s version of “Creole Belle” from a live performance.

My Creole Belle, I love her wellMy darlin’ baby, my Creole Belle

When stars do shine, I’ll call her mine

My darlin’ baby, my Creole Belle.” “Up a Lazy River” was written by Hoagie Carmichael and Sidney Arodin in 1930. Here’s Hoagy’s original recording for the Victor Label. Up a lazy river by the old mill run

That lazy, lazy river in the noon day sun

Linger in the shade of a kind, old tree

Throw away your troubles, dream a dream with me.

Up a lazy river where the robin’s song

Greets the bright blue morning, we can roll along

Blue skies up above, everyone’s in love

Up a lazy river with me. “The Sheik of Araby.” was a melody written by Ted Snyder in in 1921. He called it, “The Rose of Araby.” A friend had just read the book, The Sheik and suggested he change the title, but Ted saw little sense in that, until he saw posters for the Rudolph Valentino film. Harry B. Smith and Francis Wheeler wrote the lyrics. F. Scott Fitzgerald included a verse in his novel, The Great Gatsby. Here’s a very early version of the song from 1922 by the Regal Male Trio. And here’s a later, instrumental version featuring Stéphane Grapelli and Django Reinhardt. I’m the sheik of Araby, your heart belongs to me.

At night when you’re asleep, into your tent I’ll creep.

The stars that shine above, will light our way to love

You’ll rule this land with me, I’m the sheik of Araby. “Bill Bailey” was written by Hughie Cannon in 1902 about his friend, Willard Bailey and his wife Sarah. Here’s Big Bill Broonzy singing “Won’t You Come Home Bill Bailey?” with some fine fingerstyle guitar accompaniment. Won’t you come home, Bill Bailey?

Won’t you come home.

She moans the whole night long.

I’ll do the cookin’ honey, I’ll pay the rent

I know I done you wrong.

Do you remember that rainy evening, I threw you out?

With nothin’ but a fine-toothed comb

I know I’m to blame, ain’t that a shame

Bill Bailey won’t you please come home? “Darktown Strutter’s Ball” written by Shelton Brooks in 1917 and popularized by Sophie Tucker. Here’s a version of “Darktown Strutter’s Ball” recorded by Fats Waller. In the interest of the history of the jazz age, one hopes to be forgiven for any offense caused by the title. It is a glimpse of the time. I’ll be down to get you in a taxi honey

Better be ready ‘bout half past eight.

Now honey don’t be late

I want to be there when the band starts playin’

And remember when we get there honey

Two steps I’m gonna have ‘em off

I’m gonna dance off both of my shoes

When they play those Jelly Roll blues

Tomorrow night at the Darktown Strutter’s Ball. For our recording, Peter Davis plays clarinet and tenor banjo, Scott Fore plays guitar, Glenn Fukunaga plays bass, Paul Pearcy plays drums, Cindy Mangsen sings harmony, George Gillette plays piano, and I play rhythm guitar and sing.

From the novel:

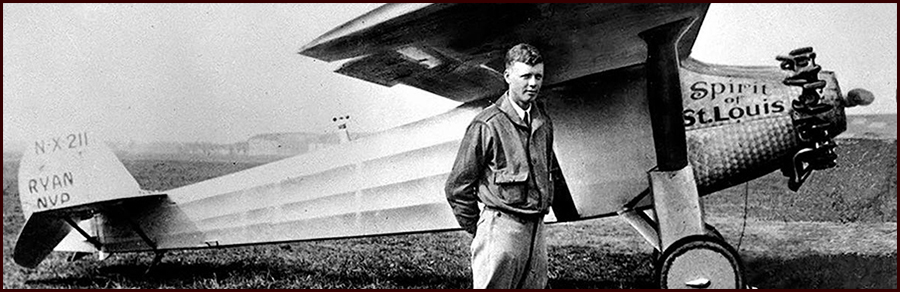

After what was a pretty sleepless night, Charles Lindbergh brought his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, over to Roosevelt Field on Long Island on the morning of May 20th, 1927 to begin the odyssey that would make him a world-famous hero and would change history. There was a light, drizzly rain over the field, but weather reports for the skies in the East were encouraging for his flight across the Atlantic as he was to make his way to Paris.

The Spirit of St. Louis was built for him by the Ryan company in San Diego. A group of friends, basically the St. Louis Raquette Club operating as the Spirit of St. Louis Organization, had contributed roughly one thousand dollars apiece to buy the airplane which cost just under $12,000. He contributed $2,000 of his own saved from his earnings as a pilot for the air mail service.

The flight would take more than thirty-two hours. He would have to switch between five fuel tanks to balance the plane. He had specified that the main fuel tank was to be mounted in front of him just behind the engine. This meant that he had no forward vision, but he didn’t want to be in between the engine and the fuel tank if case of a crash. He had 425 gallons of gas which he calculated would give him the 3,600 miles he would need plus about a ten percent margin. The most dangerous part of his flight would be taking off with such a weight of fuel. After that, falling asleep was probably his greatest concern. Just before eight AM, he climbed aboard and took off. Lindbergh’s mother, Evangeline, had visited with him the day before he began his flight, and she had wished him good luck as she boarded the train to head home. She was a high school teacher in Detroit and was back in class as school began Friday morning. She asked her principal not to mention anything about the flight to the students. But as she walked to the small cafe where she normally had lunch she was mobbed by well-wishing students and reporters. She realized that she would have to make a statement. She said, “Tomorrow, Saturday, a holiday for me, will either be the happiest day of my whole life, or the saddest. Saturday afternoon at three o’clock I shall begin looking for word from Paris – not before that.” Then she added, “Until then, my heart and my soul is with my boy on his perilous journey.” Lindbergh flew out over Long Island Sound and crossed the Connecticut River, then Rhode Island and Massachusetts and on across open water toward Nova Scotia. His last point of reference was the coast of Nova Scotia, and he was pleased to see that his compass and his dead reckoning had put him pretty nearly where he wanted to be. From there he was over open ocean until the reached the coast of Ireland near Dingle and veered south over England and on to Paris where he circled the Eiffel tower before heading to Le Bourget Aerodrome. Aside from terrible difficulty in keeping awake, he encountered a buildup of ice on the wings and struts that threatened to bring him down. He was able to maneuver through the clouds to find some clear air and succeeded in reducing the ice. When sleep became a real emergency, with accompanying hallucinations, he would descend to within a few feet of the water and let the salt spray hit his face to shock him back to wakefulness. He reported experiencing ghosts moving in and out of the tail of his plane. Just a few hours into his flight, the news services began to report on his progress. The bulletins were just speculation, since there was no way to know where he was on his flight; until a ship, the Hilversum, five hundred miles off the Irish coast, reporting sighting his plane. Then it seemed that everybody in the nation was waking up to the importance of this event, and all of us started to tune in for any news. When he was sighted over the French coast, the anticipation turned to pandemonium, as we all realized that he had ‘made it!’ On the morning that Lindbergh took, off there were two other planes ready to make the attempt. One was the Columbia which was to be piloted by Clarence Chamberlin and Lloyd Bertaud, and the other, the America with Lieutenant-Commander Byrd and a co-pilot. Byrd was on hand at Roosevelt Field preparing his own plane, and saw Lindbergh barely miss a tractor and come within twenty feet of some telephone wires as his heavily laden craft ascended into the first rays of sunlight. He said, “God be with him.” Sadly, one contender, a French team in a Levasseur biplane named L’oiseau Blanc, who would have been first to make the crossing, having left Le Bourget on Sunday, the 5th of May, disappeared somewhere in the Atlantic. All were contending for the distinction of being the first, but also were drawn to the $25,000 prize that was offered by a wealthy hotel owner named Raymond Orteig in 1919 for the first non-stop flight between New York and Paris. The prize hadn’t specified that the pilot had to be alone. Writing about it later, Lindbergh became quite poetic in describing his sense of the man and the plane as a team. “The airplane was no longer an unruly mechanical device, as it was during the takeoff, rather, it seemed to form an extension of my own body, ready to follow my wish as the hand follows the mind’s desire — instinctively, without commanding, more like a living partner in adventure than a machine of cloth and steel.” The achievement became the greatest event in anyone’s memory. One paper devoted one hundred column inches to his story. Another paper said that he had performed “the greatest feat of a solitary man in the records of the human race.” President Coolidge sent a cruiser of the United States Navy to bring him and his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, back from France. Western Union provided a form for people sending their congratulations and 55,000 telegrams were delivered to him in a truck. One telegram from Minneapolis was signed with 17,500 names and made up a scroll 520 feet long. Ten messenger boys carried the unrolled scroll in the parade in Washington. After the public welcome in New York, the street cleaners swept up 1,800 tons of paper compared with only 155 tons after the Armistice parade. The flight certainly captured my imagination. I was sort of an armchair pilot in my way. I had followed the progress of the conquest of the air since the first reports of the Wright Brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk. I had read the reporting on the battles of the war which focused on the advances in military planes; the first use of airplanes as bombers and the exploits of the flying aces and their dramatic ‘dog fights.’ I would often read to our son, John, from the newspaper when he was still quite young. Heroic exploits of the pioneers of aviation always seemed like an occasion for discussion. But he was only seven when Oakley Kelly and John Macready completed the first nonstop coast to coast flight from New York to San Diego in May of 1923. We did walk down to the post office to buy the new ten-cent airmail stamp, when the government issued it in February of 1926. He was somewhat impressed when we read of Commander Byrd and Floyd Bennett and the first flight over the North Pole on the day after his eleventh birthday in May of 1926. But having just turned twelve when Lindbergh made his heroic flight, none of the drama was lost on him. From then on, airplanes were objects of fascination. Lindbergh was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Congressional Medal of Honor, and innumerable foreign decorations and honorary memberships. The U.S. Army commissioned him with the rank of Colonel. He was offered two and a half million dollars for a tour of the world by air and was offered $700,000 to star in a movie. A town in Texas was named for him, and a large number of streets, schools, restaurants, and, of course, the dance, “the Lindy Hop” were all given his name. Lorraine expressed the thought that the ‘hop’ was not just the dance, but the flight too. Meanwhile, 1927 was turning out to be a big year for the Whiteman orchestra and it meant some travel time for me. We were to spend more time in the studio in Chicago. The 20th Century Limited only took 20 hours from Grand Central to the La Salle Street station in downtown Chicago. I was pretty used to the routine, arriving just before ten in the morning. If it was a nice day, I would walk over to the hotel on Van Buren. It was Bix Beiderbecke who introduced Whiteman to a young friend named Hoagland Charmichael. Hoagy had first met Bix in 1922, when both were students. I think Bix might even have still been in high school. The two became friends and played music together. Hoagy’s one credit, the song, “Washboard Blues” had been recorded by an unknown band, Hitch’s Happy Harmonists, with Hoagy on the piano. Whiteman liked the tune and said that if it had lyrics, he would record it. Around 1923, on a visit to Chicago, Bix had introduced him to Louis Armstrong, and the King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band. Armstrong would be a great influence on Hoagy’s and Bix’s music. Louis Armstrong would come to have a great affection for Bix and spoke highly of his playing. Clearly influenced by Armstrong, Bix did have his own, sweeter, less punchy style, and of course, amazing control and tone. Hoagy Carmichael’s first recorded song, initially titled “Free Wheeling”, was written for Beiderbecke, whose band, The Wolverines, recorded it as “Riverboat Shuffle” for Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana in 1924. His other early musical compositions included “Washboard Blues” and “Boneyard Shuffle.” The instrumental rendition of “Washboard Blues,” recorded in May, 1925 at the Gennett studios, was the earliest recording in which he performed his own songs, including an improvised piano solo. It was also there that he recorded “Star Dust,” one of his most famous songs, in October of 1927, playing the piano solo himself. In 1929 the name of the song was changed to “Stardust.” The Gennett Company had become an important label and studio. They had released the most complete catalog of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, featuring Louis Armstrong, in 1923. Bix and Frankie and Jelly Roll Morton had all taken that five-hour train ride from Chicago. Richmond was what was known as a ‘sundown town.’ No Negro would dare to be out in public after sundown, and the fact that Negro musicians would risk a journey into that territory was an indication of how highly they thought of the Gennett label. Recording there was difficult as well. When Armstrong first went there they were still using the mechanical method with the large cornucopia or ‘witch’s hat.’ The musical wave was etched into a wax cylinder, and that meant that the studio had to be kept warm. Sweat dripped from their faces and their instruments, and it was doubly exhausting. William Jennings Bryan recorded his “Cross of Gold” speech there in 1923. The speech had caused a sensation at the Democratic convention in 1896, and Bryan had given the speech many times over the years. In it he spoke up for silver coinage and ‘bi-metalism,’ as opposed to the gold-only legislation of 1873, known as the ‘crime of the century’ because its passage favored the bankers against the common man. Gennett was also the official recording company of the Klu Klux Klan, and many of its employees, not to mention the town’s civic leaders, were Klan members. The recordings produced for the Klan included traditional hymns with new lyrics celebrating white supremacy and the exhortations of a wrathful god. One of the songs was called, “Johnny, Join the Klan.” Southern Indiana was a hotbed of Klan activity, and the Klan had had a dramatic resurgence following D. W. Griffith’s horrible film The Birth of a Nation. At first Whiteman had offered Hoagy the chance to sing “Washboard Blues.” But he began to have second thoughts about it. Hoagy had a somewhat charming, ‘folksy, but unimpressive voice.’ Whiteman asked Bing to take his place. Bing approached Hoagy warily, saying he would like to learn the song, and Hoagy suspected that Whiteman had changed his mind. But he was magnanimous, he realized that it was a lot to expect that he could just step into the lead of a Whiteman recording. Hoagy said that he never thought of himself as a writer. He was convinced that someone like him could never write a really good song. He loved to play the piano, and he loved to sing, but he held the great standards in such reverence that he never allowed himself to believe that he could create one of them. It was when his trio played for a private party at the home of a New York millionaire named Carlisle in 1922 that he first had a chance to be with some of those talented and celebrated people. Florenz Ziegfeld was there and also Irving Berlin. Somebody asked Irving Berlin to sing, and he sat down at the piano to play some of his well known songs. Haogy said, “The guy played the piano, so-so, and he sang so-so, but nothing special, and all of a sudden, I said to myself, these people who I always thought were so out-of-this-world, are human, just human. I could play piano better than this guy, and I could sing a song better than this guy. From that point on he allowed himself to do the work of writing a song, not feeling that he had to do something superhuman, but just good hard work. He was no longer in awe of the greats, but saw a way for him to do the work of a songwriter one song at a time. He had discovered his own method of songwriting, which he described later. "You don't write melodies, you find them. If you find the beginning of a good song, and if your fingers do not stray, the melody should come out of hiding in a short time." In the Fall. Whiteman negotiated with Carl Laemmle at Universal Pictures to produce a film to be called, King of Jazz. They scheduled production to begin the following March. Jimmy Gillespie signed the contracts when he and Laemmle met at the Harmony Club in New York. Just before the end of the year, an opportunity came up for the orchestra to work with Florenz Ziegfeld. Celebrating the first anniversary of his production of Show Boat, Ziegfeld launched two new shows. One, an Eddie Cantor musical called Whoopee, at the New Amsterdam Theater, and a completely revised version of his after-hours nightclub review, Midnight Frolic, on the New Amsterdam Roof. Show Boat had been a breakthrough in many ways. Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein, with some help from P. G. Wodehouse, had created a challenging drama which for the first time mixed white and Negro players on a major Broadway stage. Based on the book by Edna Ferber, it dealt with themes of racial strife and miscegenation. The song, “Old Man River,” sung by a Negro stevedore, conveyed the despair of oppression. It was an intrepid departure from Ziegfeld's formula of light comedy and scantily-clad young women. But with these two new productions on his hands, Ziegfeld called on Whiteman for help. The musical director for Whoopee, George Olsen, had been fired in a dispute over special arrangements he had created and other preferential treatment for the leading lady, Ethel Shutta, who was also his wife. Ziegfeld, in a pinch, hired Whiteman to take on both shows at a salary rumored to be the highest ever offered a bandleader. On December 29, Whiteman began his stint with Whoopee. Several disasters befell the production, but nothing diluted the holiday merriment and enjoyment of the spectacle for Lorraine and me. One of the disasters involved Charlie Margulis, our lead trumpet. In the spirit of the occasion he had imbibed a little more than he should have, and when the band began one dance piece, Charlie started a different piece. Oddly, he pushed ahead playing louder, and then louder still. Uncharacteristically, and probably because of the extra pressure of opening night, Whiteman blew up. “Get me a pistol. Somebody kill the son of a bitch. I’ll tear him apart with my hands.” As if that episode weren’t enough, this theater had a moving stage which could roll out over the orchestra pit. Whiteman wasn’t aware that that was going to happen, and as he conducted the finale, it began to move toward him. He ran out of the way, but then, he couldn’t get back into the pit. Eddie Cantor, who had written the show and had the starring role, took the opportunity to improvise a very funny imitation of Whiteman, using a drumstick for a baton. When the wild goings on ended and the audience finally let us all go, we took the elevator to the lavish roof for the “Midnight Frolic.” The kitchen offered an outstanding menu, with prices to match. Many of the Ziegfeld stars, including Fanny Brice and Helen Morgan, sang a number or two, but Whiteman was splendid in the nightclub setting, and you could tell he was relieved to have the orchestra pit episode behind him.© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

To Track 13. “The Man Who Loves a Train".

Charles A. Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis.