The Man is an audio novel set in the first decades of the 20th century

The stories and original songs are written by Steve Gillette

Track 2. “St. Louis Blues and Jada”

Narration:

But Danny was a troubled kid. For a homeless child, the streets of New York in the eighteen-eighties was a pretty rough place. The old Five Points district was a perfectly good slum before it crumbled into the swamp and served mostly as a dump. Mary worked for the Quaker charities and they asked her to find a home for Danny, but there was nobody else who could take him. She asked Jack what he thought. Jack took one look at Danny, and he knew they had to help him.

But Danny was a hard case; it took a long time and a lot of patience. Finally Mary taught him to read, but that was a slow process. For hours he would curl up and listen to Jack play the piano. Danny always said it was the music that really brought him into the world. Jack was very good with him, he’d correct him gently, he’d say things like, “Nobody’s gonna want to play chess with a twelve year old who thinks the king can do anything he wants.”

Danny’s first instrument was a beat-up old guitar, and he played that like a drum with strings for the longest time. Learning to play the guitar from two piano players gave his style some quirks. It’s the drive of that old stride piano that you can hear him reaching for. The instrument itself is just pieces of wood and steel, but when one string begins to ring with another, it changes something. It doesn’t change time itself, but it changes the way we perceive time. It brings us to the moment, liberates us from anxiety, opens us up to transcendent joy. As Danny would say, “You have to be present to play.” And play they did.

© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

The Music:

"St. Louis Blues" was written by William Christopher Handy and published in September 1914. He wrote an autobiography in 1941 called The Father of the Blues which gave very clear insights to how this song came to him. In it he says that he had been inspired by a chance meeting with a woman on the streets of St. Louis, distraught that her husband had abandoned her. She lamented, “Ma man's got a heart like a rock cast in de sea.”

In 1903, while waiting for a train in Tutwiler, in the Mississippi Delta, he had the following experience: “A lean loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. The singer repeated the line three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.”

Handy noted square dancing by Mississippi blacks with “one of their own calling the figures, and crooning all of his calls in the key of G.” He remembered this when deciding on the key of “Saint Louis Blues.” “It was the memory of that old gent who called figures for the Kentucky breakdown; the one who everlastingly pitched his tones in the key of G and moaned the calls like a presiding elder preaching at a revival meeting.”

Except for the unusual verse and a sixteen bar bridge, “St. Louis Blues” is in the classic twelve bar blues form. Many believe this structure comes out of the field hollers, the work songs of slaves and chain gangs. Some of the work was rhythmic like driving spikes on the railroad, or hoeing a row of corn, but there is also the tradition of stating a line and then repeating it. Handy wrote: “I adopted the style of making a statement, repeating the statement in the second line, and then telling in the third line why the statement was made.”

He wrote about some of the musical characteristics of these blues songs: “The primitive southern Negro, as he sang, was sure to bear down on the third and seventh tone of the scale, slurring between major and minor. Whether in the cotton field of the Delta or on the Levee up St. Louis way, it was always the same. Till then, however, I had never heard this slur used by a more sophisticated Negro, or by any white man. I tried to convey this effect by introducing flat thirds and sevenths (now called blue notes) into my song, although its prevailing key was major — and I carried this device into my melody as well. This was a distinct departure, but as it turned out, it touched the spot.”

Regarding the “three-chord basic harmonic structure” of the blues, Handy wrote that the “(tonic, subdominant, dominant seventh) was that already used by Negro roustabouts, honky-tonk piano players, wanderers and others of the underprivileged but undaunted class from Missouri to the Gulf, and had become a common medium through which any such individual might express his personal feeling in a sort of musical soliloquy.”

But St. Louis Blues also has a 16-bar bridge written in the Habanera rhythm, (I’m guessing that refers to Havana) what Jelly Roll Morton called the “Spanish tinge.” The tango-like rhythm is notated as a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note and two quarter notes, with no slurs or ties. It is played in the introduction and in the bridge.

Handy said his objective in writing the song was “to combine ragtime syncopation with a real melody in the spiritual tradition.” Handy attended the 1893 Chicago World Exhibition where a number of other yet-to-be-famous players and composers gathered. Scott Joplin was there, too. There is no evidence that they met, but it’s likely.

Handy eventually became a publisher. He encouraged performers such as Al Bernard, “a young white man” with a “soft Southern accent” who “could sing all my Blues.” He sent Bernard to Thomas Edison to be recorded, which resulted in “an impressive series of successes for the young artist, successes in which we proudly shared.” Handy also published other Bernard compositions, including “Shake Rattle and Roll” and “Saxophone Blues.”

“Ja-da” was written in 1918 by Bob Carleton. The title is sometimes rendered simply as “Jada.” “Ja-da” has flourished through the decades as a jazz standard.

Carleton wrote the 16-bar tune when he was club pianist in Illinois and first popularized it with singer Cliff Edwards. The sheet music for “Ja-da” was published in 1918 by Leo Feist, Inc., New York. The sheet music proclaims that “The sale of this song will be for the benefit of the Navy Relief Society” and adds “The society that guards the home of the men who guard the seas.”

The performance you hear here is by my dad, George C. Gillette with Jack Williams playing rhythm guitar.

From the Book:

That stride left hand has been the heartbeat of my playing for as long as I can remember. The guitar is really a drum, anyway. It’s true that changing the position of the fingers on your left hand, you can make that drum seem pretty musical.

I can keep two or three voices chunking along in the pocket till the cows come home, but I’m always looking for ways to sail off with the melody and beyond. Over the last forty years or so, I’ve heard some wonderful players take that search into some interesting territory.

Jack was an old barrel house player. Politeness forbids me mentioning some of the other places he played, but the piano was the thing that rescued him from starvation and pulled his life back together after a shaky start as orphan and runaway, sailor, and briefly, a convict.

Johnny’s mom had a lot to do with rescuing Jack from a bad end. She worked in a library to make a living (only men were librarians then). As a Quaker volunteer she worked with prisoners trying to extricate themselves from the iron fist of the military tribunal. Johnny’s dad had refused orders in some complicated goings on in Central America, what Mr. McKinley eventually called, “Gunboat Diplomacy.”

Jack didn’t mind playing for the officer’s club dances, but suppressing rebellious Hondurans with a Gatling gun didn’t seem to him to be something he should be asked to do. For him the Halls of Montezuma were a personal labyrinth. He finally stood his ground when he felt he had obeyed one too many orders. He probably didn’t realize the consequences of taking such a stand. But then, he never quite got the hang of compromise.

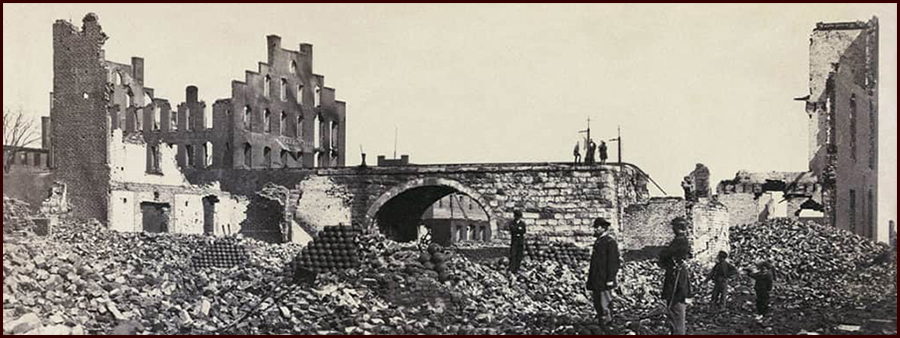

We’ve always celebrated his birthday in April. Everybody always said that they thought he was born around the time of the fall of Fort Sumter in April of 1861. During the conflagration that ensued, so many lives were disrupted and so many children were set adrift. When the Union soldiers discovered the atrocity of Andersonville, all compassion was abandoned.

In the sodden ashes of a destroyed rooming house, Jack was found and turned over to a widow woman who took in several orphans. To keep body and soul together she put the little ones to work on a tenant farm on the land that used to belong to her slave masters.

Grace Morrow was an octoroon, raised by her masters, the Saxons, as one of the family, which I suppose she really was. She taught Jack to play some of the 'sacred' songs on an old pedal organ rescued from the ruins of the home place.

She had been married to a free black man, who only survived emancipation by two years. The Emancipation Proclamation left some things to be desired. It didn’t abolish slavery; it only threatened to free the slaves in the states that were in rebellion.

One can understand how the British would not have been supportive of the compromises that Lincoln had to make in navigating the nation through the emergency of war. In a cynical article in the London Spectator it said, “The principle is not that a human being cannot justly own another, but that he cannot own him unless he is loyal to the United States.”

People scrabbling to put lives back together in the wake of Sherman’s ‘March to the Sea’ and its resulting starvation and disease, weren’t concerned with such distinctions. Oddly, February 1865 is the only month in recorded history not to have a full moon.

The ‘Widdy Murra’ was known to all as a quiet, practical woman who could be a mama tiger for her chargelings. There were half a dozen little foundlings that would follow her around like chicks. One of these was Jack’s first love.

Though none of them were really related, the little family of castaways pulled together, and truly did scratch at the earth to survive. It was a sharecrop subsistence, overseen by the landlords, young Mr. Saxon and his brothers.

As Jack got into his teens he was especially fond of one little brown eyed beauty that they called Amber. They stuck up for each other, and played hide and seek in the thicket, and when they started to discover more tender feelings, it just made sense to everybody that they would be together.

But Jack was just an orphan chore boy, he had nothing to offer a wife, and worse, he had a rival. One of the younger Saxon brothers, Terrence, was saying that it wasn’t right for Jack to be forcing his affections on his own sister, but nobody who knew the young folks took that point of view. Heck, they’d known them all their lives.

One day, Terrence and a couple of the mill boys stopped Jack on the road and beat him up pretty bad and put him in a boxcar with a strong rope. In the midst of their frantic blows and kicks, Jack heard one of the mill boys shouting, “he's a Levite, he's brought the punishment on himself.” To this day, he does not know what was meant by that unless it was a reference to the condemnation of incest in Leviticus.

They put a little tar at the knots and feathers in his mouth and ears to discourage him from thinking about coming back. He always said it was a brand new boxcar, smelled like fresh cut pine. Other than a few burns and a couple of broken bones in his right hand he wasn’t hurt badly. It was mostly the sadness that stayed with him.

He had quite a lot to contend with just keeping alive. Those were terrible times in this country. There were lots like him, hoe boys down on their heels, hungry and hopeless. He finally landed with a tent revival show playing the gospel tunes. From there he drifted through traveling shows, the gin mills and the bawdy houses.

By the 1870's the Women’s Christian Temperance Union began to be force in social affairs. But their influence was more to be felt in the major cities. Jack's teen years were spent in the most deplorable and at the same time colorful surroundings.

The driving rhythm of his left hand was as valuable as a boxer's jab in providing for him, and he learned to take command of any opportunity to fill the space with music wherever he found a piano. It was a judge in Panama Beach who suggested that he take some time off to go to the finishing school that was run by the U. S. Navy, and that took him to lots of interesting places.

I’d love you to hear him play. He’s ragged, but right, like the sound comin’ out of a beat up saxophone with a few rattles and a proud old tone. He never quite grew up; life kicked him around quite a bit, but he and Johnny’s mom always let Johnny know that together they had made the world a better place and they put him right in the center of it. I’m sure they saved my life as well.

© 2012, Compass Rose Music, BMI

To Track 3. “Cordovan Boogie".