The Man is an audio novel set in the first decades of the 20th century

The stories and original songs are written by Steve Gillette

Track 3. “Cordovan Boogie”

Narration:

Johnny was getting quite a reputation as a player when he was just a teenager. You could hear the influence of Old Jack, but Johnny had taken it to a place of his own. He and Danny were hired to play for a homecoming party in October of 1900, and the guest of honor turned out to be Samuel Clemens.

Mr. Clemens was a fan of the stride players. He recorded the boys on one of Mr. Edison’s cylinder machines. You could say that he and Edison were the first collectors of Jazz recordings. But Edison said that he played his jazz records backwards because they sounded better that way.

Years later Danny worked for Paul Whiteman as a coach and an arranger. He wrote charts for many of the greats, but he would hold off releasing anything until it had the benefit of Johnny’s interpretation. He would always say that Johnny makes it presentable.

© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

The Music:

“Cordovan Boogie” Again we recognize the twelve-bar blues form. This time it’s in the key of C, and the chords are C, F and G or I, IV and V. Just about as simple and accessible as a song can be. The thing here is that as the song progresses through the pattern eight times, the players can try different ideas and bring a fresh approach to each new section.

The effect can be like a kaleidoscope of glass beads constantly shifting and changing to have a possibly hypnotic and musically joyful effect on the listener. Each of the soloists gets to have a ‘ride’ while the piano player and the rhythm section keep solid time.

‘Boogie’ usually refers to a pattern in the left hand. Often the pattern will be made up of the tonic note, C in this case and then several notes of the chord. The one, the three and the five to be sure, but often other notes are interjected into the pattern to make it more interesting. This has also been described as ‘walking’ the bass. The pattern will generally repeat four times for the first line based on the tonic chord. Then the pattern moves up to the fourth scale degree and takes place only two times before moving back to the tonic for two times through the pattern. Then two times through the pattern based on the fifth scale degree, two times on the fourth scale degree, then two on the tonic and two on the fifth.

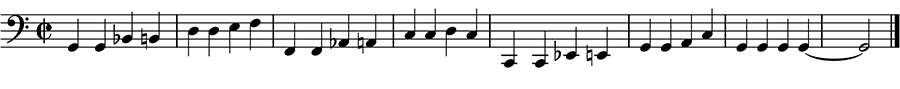

Some of these patterns can be very complex, but the idea of the continually moving walk up and down is essential. Here’s what it might look like written out. For this example I’ve used the key of C and shortened the time by half for the sake of simplicity:

When the piano player is alone, it’s more likely that he will employ a busy left hand boogie pattern. When there is a bass player and a rhythm guitar, it’s best not to over-complicate the part, to leave room for all the instruments to be heard in their own realms.

You can hear the right hand of the piano player starting each new section in a different place, sometime calling attention to the piano with a staccato phrase, sometimes with an intentional dissonance, sometimes dropping under the soloist to support and not draw attention away. You’ll even hear them all empty out at times to allow the relationships to find a new balance.

You hear the clarinet and the harmonica consciously call each other out and trade phrases. And toward the end, you can hear the players interweaving voices and phrases in a kind of ‘Dixieland’ ramble. Even a simple tune can have a celebratory effect.

Another musical element in this piece is the shuffle beat. In some boogie tunes there is a hard adherence to the straight eight-note pulse, what they call ‘eight-to-the-bar.’ This track allows the back beat to create a ‘swing,’ a slight anticipation or ‘shuffle.’ So many songs use this shuffle beat. Think of the Eagles’ song “Heartache Tonight,” or Elvis’ “Don’t Be Cruel.” Loggins and Messina’s “Your Mama Don’t Dance and your Daddy Don’t Rock and Roll” is a good example, and I suspect it owes something to the song mentioned in last week’s article, “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” You can hear the rolling triplets in the title alone.

There’s a lot more to this question of ‘swing.’ We may have occasion to discuss it again. Suffice to say that it’s a matter of style, or ‘swagger,’ definitely a physical expression of rhythm, and that probably means that it is derived from the moving body in the dance. It was Fats Waller who said, “Lady, if you have to ask, you’ll never get it!”

Randy Wolchek played piano on this track, Scott Petito played bass, Mark Graham played both the harmonica and the clarinet, and I played rhythm guitar.

From the novel, The Man:

That’s Johnny playing the piano, I’m the one trying to keep up with him on the guitar. I’m not bad, but he’s great. Jack taught us both just about everything we knew of music at that point. He still plays that old stride style like a legend.

Besides my guitar, the one possession I most prize in the world is the old Edison cylinder you’re listening to. It’s a sound recording. Amazingly, a replica of a real event. Listening to it, I’m able to relive that moment in time.

It’s scratchy, and worn, but I can hear the voices, the sound of that piano, the vibrancy of those hands on the keys. Like something trapped in amber, it’s music played in another day preserved in wax.

This recording was made by Samuel Clemens - the man we know as Mark Twain. He had one of Mr. Edison’s machines and had made quite a few recordings. He played the piano too, although I’ve never heard a recording of him playing it.

I learned recently that he had a Martin guitar that was made in 1836. That’s the year he was born, although he didn’t get the guitar until he was in his twenties. He took it with him on his lecture tours, and sometimes played it. I’d never heard his recorded voice, or had any sense of him other than the printed page.

The first time I saw one of these cylinders was when Mr. Clemens gave me this one, in October of 1900. I have since had the studio engineers make a copy for me on a record to try to preserve its precious sound. Of course, I was only a boy, nineteen myself, and Johnny too. Pretty typical tenement kids, out of what was left of the old ‘Five Points’ district. Rough times, but we didn’t know anything about that, except that the gossip was all about prices, the recession and the war in the Philippines.

Mr. Clemens played for the assembled guests and the response was very enthusiastic. You might say that was partly because he was a famous person, still, there was an undeniable joy in his playing. But then, Mr. Clemens would seek out the great players, and would learn their tunes as best he could. It reminded me a lot of our dad’s style of piano learned in some of the most disreputable places. So much of the best foot tapping music had that kind of history. It’s like the old saying, “The devil has all the good tunes.”

If Mr. Clemens had lived another twenty years, he would have loved the music of James P. Johnson, Fats Waller, Art Tatum, George Gershwin, Count Basie, Bessie Smith, Eddie Lang, Joe Venuti, Bix Beiderbecke, Tommy Dorsey, Lonnie Johnson, Billie Holiday and so many more. So much was unfolding in those first years of the new century.

He had a real ear, and an appreciation of the rhythm music that was coming out of the blending of cultures. There were traditions and musical styles brought together by migration from the South and the arrival of European immigrants. It was a wild time, probably at its wildest during the period we think of as Prohibition when the honky-tonks and speakeasies fostered a wide open feel-good era.

Back then we were just a couple of scuffling players, but Johnny was getting a reputation that was starting to open some doors to us. That night, all we knew was that we were booked to play for a homecoming party in a very beautiful town house at 14 W. 10th Street. As it turned out, it was rented by none other than the famous author, just back from seven years of traveling in Europe.

He said, “I’m Sam Clemens, and this is my friend, Dan Beard.” Well, you could have blown me over. Impulsively I said, “It’s a great honor to meet you, Mr. Beard. I know the Handy Books by heart, really!” And then, realizing that I was slighting our host, I said, “Of course, we’ve read your books too, sir.”

What an exciting time we had. Playing for a party can be lonely, like being at a wedding for someone you don’t know. But this was very different. Mr. Clemens made us feel welcome right away. He was playful and a brilliant jokester. We all shook hands and when he got to me he said, “Well my friend, it’s quite an old hand, but shake it if you must. Shake the hand that shook the hand of the man that shook the hand of Abraham Lincoln.” He didn’t explain at all, just smiled.

Mr. Beard had a violin that he had made himself. He said, “Of course, the neck’s been broken, somebody sat on it, and I had to make a new top.” Mr. Clemens said, “That’s just like my granddad's old ax, we’ve replaced the handle a couple of times, and it’s got a new blade, but it’s still my granddad's old ax.”

Mr. Beard was explaining that he enjoyed playing the violin when Mr. Clemens interjected, “But the bow! The bow! The most unaccommodating device. To put that contrivance between the player and his instrument is a cruel insinuation.” Then he added, “But having begun the journey, you’ve no choice but to continue. Follow the bow; it will lead you into strange lands. It will test your strength and your sensitivity at the same time.”

We didn’t know it then, but he and his wife, Olivia, had rented the house in New York, and purposely not returned to their home in Hartford, because that was where a great tragedy had befallen them while they were in Italy. Their daughter, Suzy, much beloved, was stricken with spinal meningitis, and succumbed while staying alone in the house three years earlier. Mrs. Clemens had returned at that time, but Mr. Clemens stayed on in Europe, unable to cancel important engagements that were just beginning to rescue the family from the financial crisis that had followed from some very bad investments.

All of this was unknown to us, and only years later did we come to realize how much history had touched our lives on that night. After food, and the music and more food and drink and more music, and cigars and stories, we felt so comfortable we had no sense of the time passing.

Mr. Clemens had been everywhere, and had seen so much of history. He said, “The forty-niners were chumps. It was the forty-eighters who got the gold. There was no law in California. The Klondike was different. The Canadian government required every miner to have two thousand pounds of supplies. They didn’t want a bunch of starving, freezing honyocks dying all over the place.”

“The merchants made all the money. They mined the miners and never even got their hands dirty.” Another thing he told us was that the gold mining in California provided reserves in the banks that helped make the North victorious in the Civil War.

We had seen the article in the Times when Mr. Clemens had returned to New York just the week before. I said, “We read what you said about the Treaty of Paris, is that where you were, in France?”

“The Treaty of Paris has nothing to do with France, it’s just the paper that purports to settle three years of the Spanish American War. Still it rages on; should I say ‘wages on’. We still have unconquered territory to subdue in the jungles of the Philippines. I just can’t accept that the people we’ve claimed to liberate must now fall under our heel. We’ve made a Faustian bargain. Twenty million dollars we paid to join the sceptered society of thieves.” By that he said he meant Spain and Germany and France with their colonial possessions.

“To defend one’s country, yes, but never to defend empire. It’s nothing more than tyranny with a price to earnings ratio. Empire is immoral.” He said, “People are being killed right now, and I can’t personally take the responsibility of doing nothing.”

“But,” we said, “You have so much power.” “No,” he said, “only the words, and only if the words have power.” Years later, I read what he had said about the importance of finding just the right word, and how the difference between the right word and the almost right word was like the “difference between lightning and a lightning bug.”

“Livy, my wife, that woman will argue both sides.” he said, “It doesn’t matter which one I agree with, I’m wrong either way.”

I asked Mr. Beard about how he became a painter. He said, “My father was a painter, a very good one. I like to think I inherited his talent. I know I got my first opportunities because of his reputation. He knew Daniel Boone. He named me after the great man. He knew Dickens too. I met Charles Dickens when he came to our house. ‘Course, I was only two years old.”

Mr. Clemens volunteered, “My father died when I was eleven, of pneumonia.” We said, “But we thought that you wrote that your father had learned so much between the time that you were fourteen and the time that you were twenty-one.” He said, “Well, I’ve been through a lot of terrible things in my life, and some of them actually happened to me.”

Mostly we talked about the music. Mr. Clemens was so pleased by Johnny’s playing and kept talking about the prospects for a “young man with his talent.” We all agreed that there was something about this emerging rhythm music that was fascinating. It was joyful, but it was also dangerously sexual and threatened to challenge the racial status quo.

Mr. Beard called it “Boogie Woogie. He said there’s a phrase, “Mbuge - Mvuge, I believe it’s from Africa.” “What does it mean?” we asked, “It’s the sound of the marriage bed.” “Oh.”

We got so much attention and praise in those early days. We thought it was because we were great. We never dreamed it might be because we were young. But we were great; we just didn’t know how great we could be. It was for us to learn from the greats, and grow beyond our youthful energy, and work for the rest of our lives on the thing that we loved, the thing that carried us through on wings of inspiration. It’s the thing that has captivated people for thousands of years, and we were privileged to be making our living at it.

Running home that night so many years ago, we could not contain our excitement. The faint roseate glow over the East River let us know that it was already the next day. Time to be whom we would become.

© 2012, Compass Rose Music, BMI

Samuel Clemens with his friend John T. Lewis.