The Man is an audio novel set in the first decades of the 20th century

The stories and original songs are written by Steve Gillette

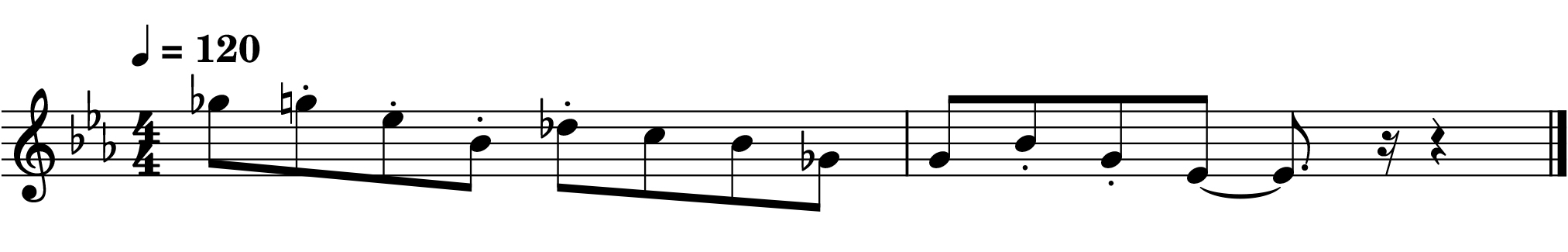

Track 10. “Basie's Boogie”

Narration:

Hammond was born into great privilege. His mother was the granddaughter of Commodore Vanderbilt, the richest man in the country when he died in 1879.

He never made a big thing about his money, but he had the funds to help out some of the musicians with a meal or a bus ticket. He paid for recording sessions and wrote articles for the first jazz magazines in New York and in England.

When he got to be old enough to drive, he bought himself a brand new Hudson convertible. He had a special car radio custom made for him by the Motorola Company. It had twelve tubes and was so powerful it could pull in stations from a long way off, especially at night.

He would often go out to his car and scan the dial. One night in Chicago he heard an amazing sound on a broadcast out of Kansas City. He tracked down the young William Basie and devoted himself to making him a star.

The Music:

This tune is another twelve-bar blues, this time in the key of D. If it weren’t for issues of copyright and catalog, the song might not be considered a song at all. More like a jam on familiar changes.

If there’s a melody, it derives from the chords without much of an assertion of individuality. This leaves the players lots of room to find their own themes and recognize and echo the themes of each other.

Randy Wolchek stands in for Basie on the piano, Rey Castillo plays drums, Scott Petito plays bass, and Bill Shontz plays saxophone.

From the book:

Riding a wave of recent success, the Paul Whiteman organization was expanding. My first role was as a rehearsal conductor and vocal coach, but many other duties followed.

For me, the job with Whiteman had come at the perfect time. The nightlife in New York was heating up and there was so much going on that it was easy to lose sight of what was important. Many temptations, not the least of which was the illegal drink which seemed to flow everywhere. For a musician it was doubly dangerous. Buying the musician a drink was a sign of respect, and who didn’t need a little respect? So many of the venues were tips only, which could generate a good living at times, but that living was unpredictable, and required the player to devote so much time to the 'life,' that most didn’t have any other.

Lorraine was so understanding and supportive, but I could never allow her to go back to full time work just so that I could be a player. Other than some private students, she devoted her time to little Johnny; she did a lot of reading, some editing, and worked pretty actively in the world of progressive political issues. This rising economy of the early twenties still left many in poverty. She helped to organize food subsistence programs and donations of clothing in that winter of ‘24.

At eight years old, our Little Johnny was quite precocious, at least as proud parents we thought so. He confronted us with the demand that we stop calling him ‘Little Johnny.’ He said it was not ‘polite.’ He had decided that he wanted to be called John. He knew that his uncle was Johnny, so this was the solution he had chosen to put the diminutive behind him for good. We understood, and controlling our laughter, we complied.

By smoothing over jazz’s rough edges, Paul Whiteman made the genre more respectable to the average listener while at the same time inviting the scorn of jazz purists. He even added jazz elements to classical music to make it more appealing to general audiences. He was truly a showman and promoter, and didn’t strain the tolerance of his audience. He did have an appreciation for the adventurism of the talented players on the cutting edge of the jazz scene, and I did also, but he was appealing to a larger and more populist audience and I could see the wisdom of that too. I suppose it’s the age-old struggle between the purist and the salesman. One critic said, not uncharitably, that Whiteman represented ’nice jazz’ to a large proportion of the American public.

Although he rarely played in public these days, he had paid his dues playing jazz fiddle and even jazz viola in the clubs in Los Angeles in the late teens. After service as a bandmaster in the U. S. Navy, he formed his own band. He was eventually able to secure a regular booking at the Hotel Alexandria in Los Angeles. The band included Ferde Grofé as pianist and arranger and Henry Busse on trumpet. This first dance band introduced Whiteman’s original brand of “symphonic jazz.” which began winning over the public and attracted famous Hollywood celebrities such as Charles Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks.

For their first trip to the East, Whiteman and his band played at the opening of the Ambassador Hotel in Atlantic City in 1920. There he attracted the attention of a Victor Talking Machine Company executive who was in the city for a company convention. They signed him to a recording contract that led to “Sandman” and “Whispering.” On the strength of that success, Whiteman moved into New York City and began a long engagement at the Palais Royal on Broadway. The next year his band debuted at the Palace Theatre.

On February of 1924, at 3:00 PM, Whiteman presented what he called, “An Experiment in Modern Music” at the Aeolian Hall. He had purposely chosen one of New York’s most prestigious concert halls, hoping to convince a possibly skeptical sophisticated audience that the music he presented was worthy of their consideration. Jascha Heifetz, Fritz Kreisler, Leopold Stokowski, Igor Stravinsky, and Sergei Rachmaninoff were among the notables in the audience. This represented a triumph of Whiteman’s prowess as a promoter, but also possibly, curiosity on the part of these giants as to what they might hear.

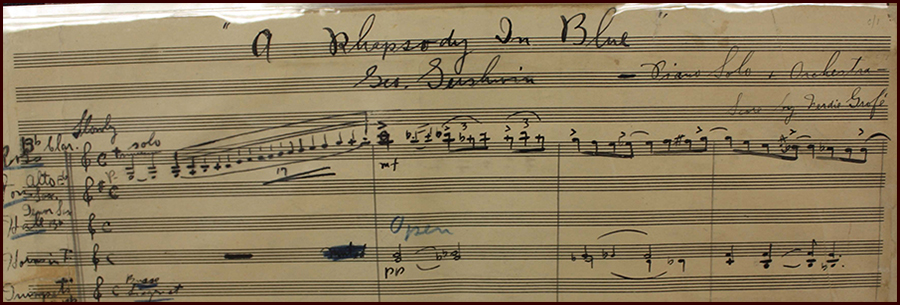

For this concert, he introduced new work from Victor Herbert and Irving Berlin, but the day featured the premiere of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” with the composer himself at the piano. Whiteman had commissioned the work a year earlier. Gershwin admitted later that he had forgotten about the piece until he read an ad for the upcoming concert. Some said he created it in just ten days. His older brother, Ira jumped in to help and together they ironed out a lot of the transitions, but still more was done even in the daily rehearsals for the big debut. It was Ira who suggested the name “Rhapsody in Blue,” George had intended “Rhapsody for America.”

It would actually be modest to say that the concert was enthusiastically received. With few exceptions everyone was enthralled. Among the major critics, Deems Taylor was effusive. He said of “Rhapsody,” it revealed “a genuine melodic gift and a piquant and individual harmonic sense. Moreover, it is genuine jazz music.” It really did establish Gershwin as a major talent, not only a writer of great popular songs, but with a patina of classical credibility.

Whiteman’s program included “Limehouse Blues,” “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” and “The Volga Boatman,” as well as some pieces composed by Victor Herbert especially for the program. Ferde Grofé had created symphonic arrangements of several Irving Berlin songs, as well as this first public performance of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody.”

Most of the rest of the program was an attempt to demonstrate the ways in which he was making the older rough-hewn, ‘discordant’ jazz more acceptable to the cultured ear. With this in mind, he opened the concert with a rowdy, barking barnyard version of “Livery Stable Blues” which had been popularized by the original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1917. He thought it would provide a contrast so that his audience would have a sense of the medium progressing to a better form. This backfired on him somewhat as many of the audience thought this selection was the high point of the concert.

Ross Gorman, Whiteman`s versatile reed man, had ten instruments on stands all around him on the stage. Gorman played a heckelphone, a baritone double reed instrument with a wonderful full voice, on Rudolf Friml`s ''Chansonette.'' I had never seen one. It was Gorman who came up with the exaggerated glissando to the opening measure in a bit of kidding, but Gershwin thought it caught the ear in a good way and encouraged him to play it up at the premiere of the piece two days later.

Roy Maxon played a crowd-pleasing trombone solo on Whiteman`s ''Mama Loves Papa,” with cornetist Henry Busse alternating riffs. This was typical of most Whiteman scores that employed pairs of soloists, whether they be brass or reed players. I especially loved the song “”Hard Hearted Hannah, the Vamp of Savannah” and Rudolf Friml’s “Indian Love Call.” Lorraine mentioned Gershwin’s “Fascinating Rhythm.” The final piece was Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” which seemed me to be a strange choice in rehearsals, but as it turned out it gave the orchestra the chance to show the full range of its powers.

On the tune “San,” there was something going on that sounded like "razzing." That was Willie Hall on the bicycle pump with a kazoo attached. He was great for gimmicks during live performances. You can see an example of his act captured in the “King Of Jazz” movie five years later. At eight years old, little John, who had seen the band in rehearsals and a few performances was still astonished by the energy and majesty of the event — the fact that he fell asleep, notwithstanding.

As for ''Rhapsody in Blue,'' the original orchestration, written for the dance band instrumentation of Paul Whiteman`s Orchestra, is a much leaner version of the piece than we are accustomed to hearing when symphony orchestras play it. Ferde Grofé, Whiteman’s primary arranger, had written a chart that featured the unusual opening of the clarinet in a long ascending wail that married the piece to the tradition of the blues and reinforced the concept of the whole program. On the way down, that wail had a more irreverent cat-call nature the first few times we heard it. It got quite a bit more refined in subsequent performances.

I recognized a riff from the old stride players early in the piece and realized that it was a sort of tip of the hat to the generation before with players like James P. Johnson and Willie ‘the Lion’ Smith. It was a turnaround riff that I had heard Old Jack play many times.

When we went in to record all the pieces for the Victor Company two and three days later, we found that we had to cut “Rhapsody” into two segments so that each could fit on one side of a12 inch 78. Even then we had to shorten each section a little, and we left out the whole middle part.

Duke Ellington’s band was playing at the Kentucky Club only a few blocks from the Palais Royale, and Fletcher Henderson`s orchestra was also nearby at Roseland. And while they both had extremely talented players and arrangers, there was not much that they were doing that would be instructive to the Whiteman band. Ellington was still essentially a stride pianist, and his orchestral style was barely beginning to emerge. The Henderson band had Coleman Hawkins in its saxophone section, a master of the tenor sax who was to influence many to come, including Lester Young, who became Billy Holiday’s musical soulmate.

It was not until Louis Armstrong joined the Henderson band eight months later that Henderson`s men began to pick up the jazz energy that Armstrong brought from Chicago and from his beginnings in New Orleans. He transformed the music of Henderson and his chief arranger, Don Redman, and influenced countless others, as well as Whiteman. Whiteman still relied on his large heavily orchestrated sound, but he longed to attract some great jazz musicians who could create the kind of excitement that Armstrong did.

Whiteman loved the great players and believed jazz was a laudable American treasure. He also believed that it was contributing to a distinctly American classical tradition, and, if anything, he erred in thinking that the classical result was the important thing, failing to acknowledge that jazz was a great medium in itself. Whiteman became one of the highest priced musical performers in the country, receiving the astronomical fee of $5,000 for a single radio broadcast. He would often brag that his own musicians were the highest paid in the business, and he afforded himself a very luxurious lifestyle.

The decade of the twenties was beginning to take on the character of ‘devil-may-care’ which was to characterize it in history. Bootleggers were fostering a counterculture of petty lawbreakers and the other kind. Jazz musicians were finding appreciative audiences in the ‘speaks.’ But with radio, records and films, and a booming economy, an industry of music and entertainment was just beginning to find its potential.

In This Side of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: “Here was a new generation, dedicated more than the last to the fear of poverty and the worship of success; grown up to find all gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.” But Amory, Fitzgerald’s protagonist in the novel, was pretty antithetical to Rainy’s ideas for our young John. She felt that his secondary characters were a lot easier to like.

This same year, a book appeared on the best seller list by an advertising man, a partner in the firm, Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn. He had created campaigns for General Motors and General Mills for whom he made up the personna of Betty Crocker.

The premise of Bruce Barton’s book, The Man Nobody Knows, was that Jesus was the world’s greatest salesman. The son of a preacher in Tennessee, Barton was a shameless promoter of what Sinclair Lewis called “The cosmic purpose of selling – not of selling anything in particular, for or to anybody in particular, but pure selling.”

He claimed that Jesus “would be a national advertiser today. I am sure, as he was the great advertiser of his own day. Take any one of the parables, no matter which — you will find that it exemplifies all the principles on which advertising text books are written.” Barton’s was one of many voices which were calling for more buying. Buying on credit, buying on margin, buying as if there was no tomorrow. It would be a few years, but tomorrow would come.

© 2012, Compass Rose Music, BMI

To Track 11, “There's a Cradle in Caroline"

Ferde Grofé’s original chart for Gershwin’s “Rhapsody In Blue.”.