The Man is an audio novel set in the first decades of the 20th century

The stories and original songs are written by Steve Gillette

Track 15. “Good Old Wagon”

Narration:

Lorraine loved it when Danny would take her out to the clubs. She would derive such energy from the music of Ethel Waters and Ma Rainey. Sophie Tucker made her laugh until she’d cry. She especially loved the music of Bessie Smith. Bessie sang with so much heart, she could tease and scandalize and seduce you all at the same time.

Sometimes Lorraine would say things that she’d heard Bessie Smith say, but she went too far one night when she whispered in Danny’s ear at the most inauspicious moment, “You’re a good old wagon, honey, but you done broke down.”

© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

The Music:

This is my re-write of a song written in 1895 by Ben Harney. It was claimed to be the first ragtime song ever published. Musically there’s no similarity, Ben’s song which can be heard here, sounds more like “Froggy Went a’Courtin’,” or “The Crawdad Song.”I always felt that the expression ‘Good Old Wagon’ combined a statement of endearment, and a wry reflection on the inevitability of the flesh going the way of all things. It’s the kind of humble Shakespeare you might have heard on the Delta or in the juke joint of some backwater.

Here are the lyrics and chords for my version:

But that

She was the

But she

And

And

You been a

Charlie Green, play that thing

I mean that slide trombone

You got the magic to make a blind man see

Make a good woman weep and moan

It's a cryin' shame what you do to my pain

When you're makin' such a joyful sound

You been a good old wagon,

Honey but you done broke down.

In the

To the

You just got to

When that old

You been a

Now that I'm out of pocket, gonna pawn that locket

And follow my freedom dreams

Gonna get myself a ticket on that southbound rocket

Out of Memphis down to New Orleans

That river's too thick to drink, too thin to plow

She's got somebody else to worry 'bout that now

A good old wagon

Honey but you done broke down.

On our version Peter Davis played clarinet, Peter Eklund played cornet and wrote the horn parts, Glenn Fukunaga played bass, Paul Pearcy played drums and Randy Wolchek played piano.

Words & Music by Steve Gillette,

© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

From the Book:

In 1930 Babe Ruth hit 49 home runs and his salary was now $80,000. When they told him he was earning more than the president, he said, “Well, I had a better year than he did.”

I had an opportunity to advise some young players about making the most of their time in a new recording studio just south of 14th Street on Seventh Avenue, and I found it to be a very satisfying few hours.

I took no money for it, but realized that I could work as an assistant engineer or assistant producer. I could coach players and songwriters, and even put them together with professionals that I had worked with over the years. And so I started accepting those jobs.

I did have a couple of notable successes, but I was happy just to be a part of something that had promise. Whatever was to come with the economy, this gave me something to show for my time and effort and what talent and experience I could bring to it. I didn't have any real sense of the upside, and was quite surprised when some of these projects actually turned into some good money.

I helped songwriters get their songs and recordings in better shape, and I was able to help publishers find talented songwriters. More and more I came to see how much development played a role in success. Who was it that first said that old thing about ten percent inspiration, ninety percent perspiration?

Another benefit was that I didn’t have to be away from home. After a couple of years, I had built a catalog of songs in addition to my own, and was having an easier time placing songs for recordings, and surprisingly, while the rest of the country was experiencing various degrees of financial insecurity, I had put aside a substantial nest egg.

Lorraine and I had expected to have to find funds for Johnny’s college tuition, since he would be graduating from high school in another year. It came as an unexpected windfall that because of his grandfather, he was a legacy candidate for Columbia. He was eventually offered a full scholarship.

On March 17, construction began on what was heralded to be the tallest building in the world. It was to called the Empire State Building. It was being built on the site of the old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street — actually the whole block between 33rd and 34th Streets.

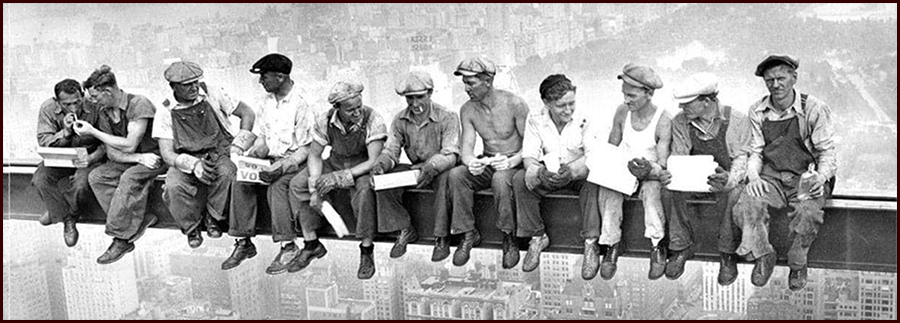

Johnny and I would walk up there on Saturday mornings to check on the progress of the massive effort. We were amazed at how quickly over the summer the building took shape. Watching the steel workers dancing on girders was breath-taking; some of those girders were still moving as the massive cranes swung them into position.

Watching gave us both pains from craning our necks, but it was hypnotic, especially as some of the details of the building's Art Deco architecture began to appear. They say that the design for the building was changed fifteen times, and some of the engineering problems raised doubts as to whether they really could build a skyscraper over twelve-hundred feet tall — 1,454 feet if you include the observation tower and the antenna.

By June 20, the building's steel structure had risen to the 26th floor, and by July 27, half of the steel framing had been completed. The crews attempted to erect one floor a day, a goal that they almost reached with their pace of four and a half stories per week.

On September 10, as steel work was nearing completion, Al Smith laid the building's cornerstone in a ceremony attended by thousands. The steel structure was topped out at 1,048 feet on September 19, twelve days ahead of schedule and 23 weeks after the start of construction. Workers raised a flag atop the 86th floor to signify this milestone.

The tower at the very top was intended to be a mast where dirigible aircraft could be docked, allowing passengers to be picked up or dropped off. On September 15, a small Navy airship tried to dock in 45-mile-per-hour winds. They narrowly avoided a disaster, and the event put an end to plans to turn the building's spire into an airship terminal.

The Empire State building opened on May 1, 1931, after only thirteen and a half months in construction. It was a marvel to us, and we took advantage of the first opportunity to wait in line for the elevator to the observation deck on the one-hundred-and-second floor. The cost of the ticket was one dollar, but the view was worth a million. We had seen Manhattan from several of the tallest buildings, but we looked down on all of them now.

The effects of the Great Depression had first begun to be felt by the public late in 1930. Hoover did very little except to wait for a recovery and attempt to reassure a panicked public. He believed in charity, but he did not believe in government relief, arguing that if the United States were to provide it the nation would be “plunged into socialism.”

When Hoover did act, it was to sever the United States from Europe, He convinced Congress to pass a new, punitive trade bill, the 1930 Tariff Act. Other nations, retaliating, soon passed their own trade restrictions. World trade shrank by a quarter. U.S. imports fell; then U.S. exports fell. To protect American wheat farmers, the tariff on imported grain had been increased by almost 50 percent.

The Ford Motor Company, which in the spring of 1929 had employed 128,000 workers, was down to 37,000 by August of 1931. By the end of 1930, almost half the 280,000 textile mill workers in New England were out of work. By 1930, more than three million Germans were unemployed and Nazi Party membership had doubled.

After the stock market crash, voters rejected both Hoover’s leadership and that of his party. In the 1930 midterm elections, Republicans lost fifty-two seats in the House. Advisers urged Hoover to address the nation in weekly ten-minute radio broadcasts, to offer comfort and solace and direction; he refused.

In 1930 J. P. Morgan offered bonds issued by the German government. They were called Gold Bonds and they offered a yield of five and a half percent. This seemed pretty good at the time since so many of the speculative instruments from the twenties had disintegrated in the crash of '29.

With the success of The Jazz Singer in 1927, a number of productions featuring sound, really the first musicals, began to appear. Within a few years, the novelty of sound had lost its appeal and the public had become jaded. There were so many of what were called ‘revues’ and, awkwardly, King of Jazz failed to distinguish itself in that category.

During its American release, King of Jazz cleared less than $900,000. Around Hollywood, the movie came to be called “Universal’s Rhapsody in the Red.” If the movie had been made on schedule it might have done very well. As it was, the public was spending less freely and the effects were starting to be felt at the box office.

Whiteman suffered another even more disastrous blow when P. Lorrillard pulled their advertising from the Old Gold Hour, and the radio show was canceled. Combined with poor box office receipts for the movie, it meant that Whiteman had to let ten band members go and cut the salaries of the remaining players by fifteen percent. I was glad that I was able to step aside without difficulty, and looked forward to a continuing but informal relationship with the band.

Bix did return to New York. He free-lanced on several sessions, playing a memorable solo on his last session as leader. The song was, “I’ll Be a Friend.” But he was in rough shape. He hadn’t kicked his drinking habit and didn’t look healthy. He had a terrible room in Brooklyn, and was altogether pretty unstable.

On the night of August 21, the man across the hall from his room heard him screaming, and went to see what was happening. He found Bix hysterical, raving about some men under his bed. His neighbor attempted to humor him by getting down on his knees to see, but he saw nothing. When he stood up, Bix collapsed in his arms. He called for a doctor, but when the doctor arrived, he pronounced Bix dead. He was just twenty-eight years old.

I spent a sad couple of days remembering so many of the great moments he brought to us. I had copies of all his recordings, some with Whiteman and the earlier ones with Hoagy and Frankie Trumbauer and Eddie Lang.

At home alone for the afternoon, I put a disc on the player. It was “Singin' the Blues” with Bix on cornet. Frankie Trumbauer played sax, and Eddie Lang played guitar. They had worked as a trio and had developed a sound that was unmistakably their own, but for this recording they had enlisted Jimmy Dorsey on clarinet and alto sax and Miff Mole on trombone. Paul Mertz played piano and Chauncey Morehouse played drums. They recorded this tune in New York on February 4, 1927. This was just before we met them.

Eddie Lang is so present with his Gibson L-5. His sense of the shuffle back-beat is evident as well. Dorsey’s clarinet solo is sweet too, and Mole’s trombone, but you can hear Bix’s character, his personality. He’s leading, but he’s listening too. It’s a wonderful thing to realize that these players will be here on these discs for all time.

In May of 1927 they recorded “For No Reason At All.” This one is just the three of them, and it’s special. Bix’s piano is wonderfully assertive, really carries the tune. He stops playing the piano at the end and picks up the cornet for the last four bars. The level jumps up, but it's still brilliant.

Hoagy Carmichael had written "Riverboat Shuffle" for Bix and the Wolverines. He called it "Free Wheeling" before Bix changed the title. This was always one of Whiteman’s favorites. Bix and Frankie and Eddie Lang again but with Don Murray’s clarinet and tenor sax, Bill Rank on trombone, Doc Ryker on alto sax, Irving Riskin on piano and Chauncey Morehouse on drums. “Ostrich Walk” was probably the same session, it’s all the same personnel and it’s a classic.

The three of them together again on “Wringin' And Twistin” from September of 1927. This one is a tune that Frankie Trumbauer wrote with Fats Waller. Bix played piano on this recording, and then again, at the end, he picked up his cornet for a flourish ending. Frankie does a lick on the sax, then Bix with his cornet, and then Eddie Lang finishes off with a quick run. Always fun to listen to these three. By now I was in tears.

Louie Armstrong particularly liked, “From Monday On.” He said, “Bix has a beautiful solo in there.” This one was recorded with the Whiteman band. Seems like Bix’s cornet had already become the ‘voice’ of the band. Bing and Harry Barris wrote the song, and it was a very big hit in 1928. It’s a big sound with so many of the full Whiteman orchestra distinguishing themselves and each other with oodles of proficiency. The five-voice men’s chorus is surprising, and deceptive of what follows. Bix jumps in with alacrity and it’s off to the races from there.

"Georgia On My Mind" was recorded in New York on September 15th, 1930 with Jack Teagarden on trombone, Jimmy Dorsey on alto sax, Eddie Lang on guitar and Gene Krupa on drums. Joe Venuti is very prominent on violin, Hoagy on the vocal, with Bix taking the last solo on cornet, and, as it turned out, his last solo on record.

Louis Armstrong was very kind to Bix in life and later in his autobiography, Singin' the Blues. He said, “Bix just didn't know how to say good night. He couldn’t offend those people who wished him well. They’d keep him for one more drink, one more tune.” Armstrong said, “they loved him so much, they killed him.”

On March 4, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt rode to the Capitol in the backseat of a convertible, seated next to Hoover. After that day the two men never met again. As Roosevelt delivered his inaugural address, he braced himself against the podium. Because of his polio and the steel braces on his legs, standing was always a cause of great pain. Attempting to reassure a troubled America, he said, “This great nation will endure, as it has endured, the only thing we have to fear is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror.”

On March 5, he asked Congress to declare a four-day bank holiday. Under the terms of the Emergency Banking Act, banks would be opened once they’d been proven to be sound. Many Americans believed that the economic crisis was so dire that it would require the new president to assume the powers of a dictator in order to avoid congressional obstruction. “The situation is critical, Franklin,” Walter Lippmann wrote to Roosevelt. “You may have no alternative but to assume dictatorial powers.”

For a long time, American reporters had underestimated Hitler. When Dorothy Thompson interviewed Hitler in 1930 she dismissed him. “He is inconsequent and voluble, ill-poised, insecure,” she wrote. “He is the very prototype of the Little Man.”

Thompson would go on to do more to raise American awareness of the persecution of the Jews than almost any other writer. Nazism she would describe as “a repudiation of the whole past of Western man,” a “complete break with Reason, with Humanism, and with the Christian ethics that are the basis of liberalism and democracy.”

Thrown out of Germany for her criticism of the Nazi government, she had her expulsion order framed and it hung on her wall. On January 30, 1933, Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. In parliamentary elections held on March 5 — the last vote the German people would be allowed for a dozen years — the Nazi Party failed to win a majority.

Six days later, Hitler told his cabinet of his intention to establish a Ministry of Propaganda. Joseph Goebbels, appointed as its head on March 13, reported in his diary four days later that “broadcasting is now totally in the hands of the state.”

Having seized control of the airwaves, Hitler took control of what remained of the government. On March 23, he addressed the Reichstag, with its doors barred. Standing beneath a giant swastika banner, Hitler asked the Reichstag to pass the Law to Remedy the Distress of People and Reich, essentially abolishing its own authority and granting Hitler the right to make law. The government then outlawed all parties but the Nazi Party.

On March 1, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., the twenty-month-old son of Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, was abducted from his crib on the second floor of the Lindberghs' home at Highfields in East Amwell, New Jersey.

The kidnapper left a ransom note demanding $50,000 in small bills. The note had some misspellings, and used the phrase, “the child is in gut care.” This last led the police to guess that the suspect might be a person of German descent. Two more ransom notes came by mail. One of them directed an intermediary, John Condon, to deliver the money to a man at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

At that meeting Condon demanded proof that the child was alive and he was told that the child’s sleeping suit would be sent to Lindbergh. Lindbergh did identify it, and a second meeting was arranged and the money was paid.

But just two days later, eleven days after the child was abducted, his body was found by a truck driver in the woods by the side of a nearby road. He had sustained a blow to the head which was believed to have been caused by a fall.

The ransom money included a number of gold certificates. Since gold certificates were about to be withdrawn from circulation, it was hoped that greater attention would be brought to anyone spending them. The bills were not marked but their serial numbers were recorded.

More than thirty months later, one of these bills did result in the apprehension of Bruno Richard Hauptman, who had used it to buy gasoline. The gas station attendant had written down the license number of Hauptman’s car, and a bank clerk had recognized that the bill was on the list of ransom money.

In a sensational trial, Hauptman was found guilty and was sentenced to death. While awaiting his execution, he turned down an offer of a large sum from one of the Hearst newspapers for a confession. He also refused a last-minute offer to commute his sentence to life without parole in exchange for a confession. He died in the electric chair on April 3, 1936. Lorraine and I were typical of parents all over the country who deeply empathized with the Lindberghs.

For school, Johnny chose to write about the similarities and differences between James Madison and Aristotle; both were considered advocates of democracy. He discovered that each was concerned that if everyone had the vote, then people would naturally vote their own interests and would demand things such as land reform and equality of wealth. Both felt that the land owning class would be more reliable in choosing what worked for the greater good of all, even though it meant the continuance of inequality.

The difference between them was in how each saw the solution to the problem of inequality. Madison advocated a system which preserved the privilege of the few by instituting the separation of powers. He believed that the Senate could moderate any overly liberal impulses of the people's house, the House of Representatives. In contrast, Aristotle believed that moving toward greater equality would alleviate the need to control the disaffected. Of course neither of them was thinking that equality meant everyone in society.

Aristotle wrote at length about tyranny, oligarchy and democracy, and clearly favored democracy. But for Aristotle the citizenry meant ‘free men,’ the land-owning and slave-owning citizens. For Madison it meant the land owners as well, but he left the slave question for a later generation. Madison was anxious to maintain power in the capable hands of the wealthy and avoid the danger of ‘too much democracy.’

Johnny wondered if this premise was too radical, and I advised him to think about his teacher and how willing he was to read a paper that explored a more contemporary view. I encouraged him not to cheat himself; he might benefit from a little controversy as long as he was respectful and earnest. We agreed that there was always a lot more to learn.

His mom pointed out that very nearly up to the present day, most people thought that wage labor was a denial of the basic right of each person to participate in the enterprise in which he worked. If one worked in a mill for instance, throughout the last century there was the expectation that he or she would take part in the profit of the mill. It was only recently that a more corporate expectation has arisen that workers must compete to be given a chance to work at all, and then only for the wage that the mine or mill owners were willing to give.

Changes in the law granted the right of 'person-hood' to corporations, resulting in unaccountable entities that could not be held responsible for their losses or liabilities. It also gave them undue influence over natural market price discovery. This created artificial scarcities, pockets of great poverty and extremes of inequality that Madison and Aristotle hadn't dreamt of. But, she admitted, that point might not be within the scope of the teacher's assignment.

© 2010, Compass Rose Music, BMI

To Track 16. “St. James Infirmary Blues"

Lunch time on the Empire State Building, 1931.