Happy Hour Words & Music by Steve Gillette and David MacKechnie

As members of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, we could order current record albums at a discount price since we were supposed to be able to cast an educated ballot for the year's Grammys. We had the privilege of purchasing LPs for, as I remember it, a dollar apiece or so. I ordered many from my heroes of the day, and devoured them learning the songs and studying the writing and production.

But the real gold mine was Aaron's Records in West Hollywood. Here record companies and distributors dropped carloads of their extra promotional copies. There were bins of eight cent, twelve cent, twenty-five cent LPs, each with a hole punched in the corner of the sleeve to discourage resale. I would come home with a huge box of these.

At that point I was interested in anything country and I found some gems; Sonny Throkmorton, Curly Putnam, and of course the Marty Robbins, Johnny Cash, George Jones perennials. I would listen for song structure, harmony, story, and especially the mythology of country music. I would pick up clues, figures of speech, traditional values and the ways that characters were developed. I wasn't exactly visiting from another planet, but I didn't fully trust myself to express compelling ideas in a country song of my own. I felt there was a danger that I might betray my own prejudices and callowness, especially my inexperience in matters of the heart as seen through the bottom of a bottle.

David MacKechnie and I met at a session of the Los Angeles Songwriters Showcase conducted by John Braheny and Len Chandler, and we began to meet once a week to discuss lyric ideas. David was more worldly, and had a familiarity with country music which helped to get us started in that 'cheatin' song, drinkin' song' genre.

An old friend of David's, Jerry Goldsmith, asked us to write a theme song for "The Outfit" a crime film with Robert Duvall, Karen Black and Joe Don Baker. Jerry had produced the music for the movie and wrote charts for our song, one that we thought captured the noir essence of the drama. We recorded onto film as they had in the old days, at MGMs legendary Studio-A where Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers had danced and Judy Garland had sung "Over the Rainbow."

We worked for several hours, experimenting with every combination of voice, piano, guitar and harmonica. In the end, they used the one with the harmonica by itself leaving our inspired lyrics on the cutting-room floor. Still, it was thrilling to go into the fabled studio lot and to the premier screening with all the cast and crew. In the room that night were the three principle stars, but also the supporting actors; Robert Ryan, Sheree North, Marie Windsor, Elisha Cook Jr., and the director, John Flynn.

David had the idea for "Happy Hour." He hit on the irony of a man discovering the faithlessness of his wife in such a 'happy' surrounding, and we took some care to evoke the 'smoky, dim lights' of a dingy roadhouse. We fabricated some subtle intimations like, 'She won't mind if I stop for just one, I can still make it home on time.' We felt we knew our hero, and could place him in a scene which would support all the elements of a story of pathos and hubris. Not exactly Greek drama, but we liked it.

On the basis of the success of an earlier song of mine, "He's Not You" which had been recorded by Anne Murray, Phil Gernhard had offered me a publishing contract with Ensign Music, the sister company of Famous Music and Paramount Pictures. The song that closed the deal was "Happy Hour." Phil had discovered a group from Florida called "Snuff" and thought the song had potential for them.

With many successful records to his credit he seemed to have all the attributes of that 'magic man' who could transform one's career if all the right pieces fell into place. You could fill a book with 'opportunities missed' stories, but suffice to say that the 'magic man' may best be sought in the mirror, while productive alliances require real-world maturity and reasonable expectations.

Phil's first success had come with Maurice Williams and the group Zodiac with their song "Stay" in 1960. At one minute thirty-nine seconds it was the shortest record ever to be number one on the U.S. Pop charts. He then went on to co-write and produce "Snoopy vs. the Red Baron." Then he produced "Abraham, Martin and John" for Dion DiMucci. Next it was Lobo's "Me and You and a Dog Named Boo" and "I'd Love You to Want Me," Jim Stafford's "Spiders and Snakes," the Bellamy Brothers' "Let Your Love Flow" and Hank Williams, Jr.'s "Family Tradition."

Phil was the son of an abusive and alcoholic father, and could be a very mercurial person himself. His approach to the recording of our song leaned on the 'gotcha' side of the irony of happy hour more than I thought was intended when David and I were exploring (and I'd have to say exploiting) the honky-tonk culture. We felt that the singer was genuinely suffering a loss, and not so much pointing an accusative finger. But my impression may be based more on what Phil had to say about his interpretation, than on what the listener may hear in it.

A typical day for Phil Gernhard started with 5:00 AM phone calls to program directors on the East Coast promoting new releases and trying to help move others up the charts. This was a high art if a brutal one. There were so many compromises and occasions for what one friend described as an 'integrity attack' that it was more than a songwriter wanted to know about how sausage is made. Still it was his primary responsibility. Producing records was always a matter of finding something that was just plain undeniable, and that's what I was encouraged to try to create. Phil was focusing on the implacable radio program director who was hard to move with anything more subtle than a grenade.

Phil's boss was Mike Curb, a wunderkind of the industry. He started out at nineteen making commercials, then writing and producing the soundtracks to low budget films and keeping the copyrights in lieu of payment. One of these was "The Wild Angels," directed by Roger Corman and featuring Peter Fonda on a Harley three years before "Easy Rider."

At that time, in addition to heading his own record company, Curb was the lieutenant governor of California under Jerry Brown. In California, the governor and lieutenant governor can be of different political parties. Governor Brown spent time outside the state on state business and at one point running in a presidential primary. This would leave Mike Curb in charge and he would sometimes use the occasion to sign executive orders of his own. As you can imagine, this practice caused some discomfort to the governor's party.

In negotiating a deal for a series of movies, he agreed to write four songs for one of the films. He was much too busy to spend time writing songs, so I was given the chance to co-write. Phil took me to meet with Curb at his home. Mike's wife proudly showed us the wall of political cartoons which vilified the young lieutenant governor. They were lovingly framed for guests to see.

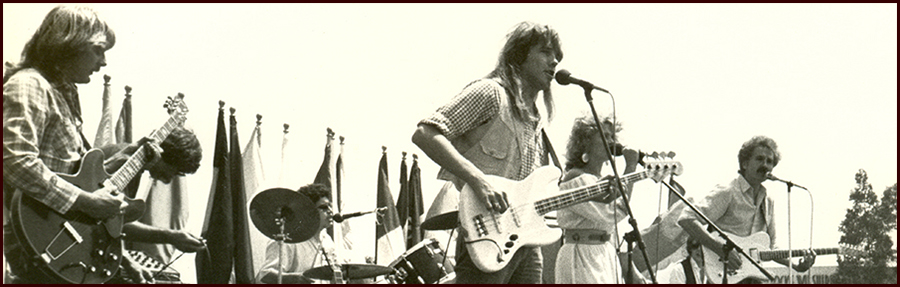

As a staff writer for Ensign Music, I had a monthly draw which covered my bills and enabled me to pay for some demo sessions of my own. It also gave me time to work on developing musical skills and collaborations. My brother Jeff and I were able to form a band with his bass player and drummer, Wayne Hartel and Rey Castillo, and we began to build a repertoire. We found ourselves playing in smoky, dim honky-tonks all over Southern California and occasionally bringing in additional players when the booking allowed for it. Tony Terborg, Greg Leise, Bruce Merion, Bill Bryson, Johnny Annelo, Yvonne McCord, Pete Grant, Brad Felton, Skip Batten, David Sproul, John Mauceri, Les Bohem and other ringers rotated in and out of our group.

As my contract came up for renewal with Ensign, my hopes for opportunity beyond songwriting were suffering some cognitive dissonance. The nature of my relationship with Phil emphasized my role as a songwriter but not as an artist. The work Jeff and I were doing as a band was not really compatible with that. As with so many opportunities it's easy to envision the break that might have come with just a few more years of faithful work, but the years were going by and patience is a thin soup, if that's not a lame metaphor. As one friend used to say, "It's OK to look back as long as you don't stare."

There were things happening on other fronts that also drew me away. At the Kerrville Folk Festival in Texas, I rediscovered the folk circuit that had nurtured my first years as a performing singer-songwriter. Spending time in workshops and singing around the campfire with Chuck Pyle, Mike Williams, Anne Hills, Gamble Rogers, Jon Ims, Steve Fromholz, Linda Lowe, Bobby Bridger, Mellisa Javors and others, I was, in a sense reborn.

In Bill DeYoung's biography, "Phil Gernhard, Record Man" he recounts that "Gernhard died in 2008 at age 67, so estranged from family and friends that he willed his considerable estate to a long-lost high school girlfriend. But before that sad ending, he had a decades-long, successful career as a music producer and promoter, starting in Florida and moving to Los Angeles and Nashville, studded with an array of number one records."

In the meantime, our song "Happy Hour" had made its way into other realms. Songs often have a life of their own. Among those who had connected with it was Ted Hawkins. He was a powerful singer, and a powerful presence. Born in Biloxi, Mississippi in 1936 he lived a difficult early life. He landed in reform school by age twelve. He later drifted, hitch-hiking across the country for the next dozen years, earning several stays in prison including a three-year sentence for stealing a leather jacket as a teenager.

We used to rent roller skates on the boardwalk at Venice beach and often saw Ted Hawkins busking. He had a thrilling, gruff and soulful voice - solid country, much like Charlie Pride. Somewhere he had encountered our song and had made it his own. The only critical thing that I would say about the man, besides his claiming to have written the song, was that he neglected to play the II major chord at the point in the song where the lyric says, 'the jukebox by the door,' and again in the second verse at 'made you blue.'

In the key of G where we sing it, the II major chord is A, and as I've written about in earlier articles, this acted as a secondary dominant, pointing to the D or D7, the dominant chord of G. It serves to heighten tension at that point of the song. It's one of those devices that I believe makes a song unique, even though it's a device that is used quite often.

Ted wore a glove on his left hand, which may have been because of some repetitive motion injury. He said that he couldn't play the blues because the glove made it hard for him to bend the strings, and that may have been part of the reason for his not using our 'money chord.'

He developed a following of locals and tourists who would come to hear him, sitting on an overturned milk-crate. He'd play blues and folk standards as well as a few original tunes with his signature open guitar tuning and raspy vocal style. Hawkins claimed the rasp in his voice came from the damage done by years of singing in the sand and salt spray of the boardwalk.

Musicologist and blues producer Bruce Bromberg recorded a dozen songs with Ted, but lost contact with him. When he re-located him he got him to agree to release the songs as an album. "Watch Your Step" came out on Rounder Records. This debut album was not successful commercially, but received a rare 5-star rating in Rolling Stone Magazine.

In the early '90s, Ted agreed to record an album for Geffen Records and producer Tony Berg. This first major-label release, titled "The Next Hundred Years," brought national attention and respectable sales. Ted began to tour on the basis of this success, commenting that he had finally reached an age where he was glad to be able to sing indoors, out of the weather, and for an appreciative crowd. Sadly, he died of a stroke at the age of 58, just a few months after the release of his breakthrough recording. (These last few paragraphs are based on notes posted on YouTube from a fan website which is no longer active at: www.the-bunker.org)

Here's Ted Hawkins singing "Happy Hour"

Ted Hawkins singing "Happy Hour"

And here's Ted in the video taken on the boardwalk at Venice Beach where he interrupts a group singing the song to claim that he wrote it and that he will show them how it should go. It's a charming view of the man, although I like what the group was doing when he came up to them. That tempo had a very nice feel to it.

Ted Hawkins in the video taken on the boardwalk at Venice Beach

Here's the recording by the group Snuff produced by Phil Gernhard.

The group Snuff performing "Happy Hour," produced by Phil Gernhard

The songbook with the sheet music for "Happy Hour" and 46 other songs is available here.

And here are the lyrics the way we sing it.

Welcome to Happy Hour Blinkin' on the neon sign She won't mind if I stop for just one I can still make it home on time. As my eyes grow accustomed To the smoky, dim lights I see the jukebox by the door And there she is, in another man's arms Slow dancin' across the floor. So this is happy hour Two drinks for the price of one People laughin' and having fun What a great place to be. Welcome to happy hour They gather here every day Cheatin's one of the games they play And this time it's on me. You're dancin' and your eyes are closed I wonder what world you're in. What will you tell me when you get home Where will you say you've been All the songs and laughter And his pretty words Take away whatever made you blue But what will you do When the fun is all over When there's nothing left of us but you. So this is happy hour Two drinks for the price of one People laughin' and having fun What a great place to be Welcome to happy hour They gather here every day Cheatin's one of the games they play And this time it's on me.

© 1983 Ensign Music, BMI / Lion's Mate Music, ASCAP

Jeff Gillette, Rey Castillo, Wayne Hartel, Yvonne McCord and Steve Gillette